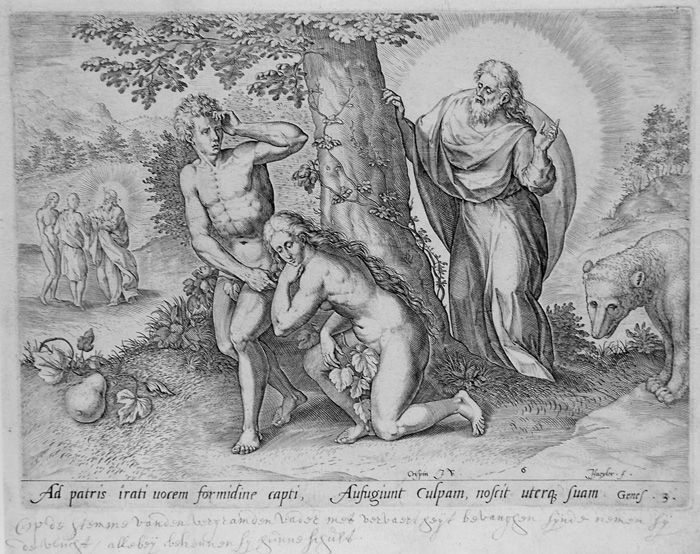

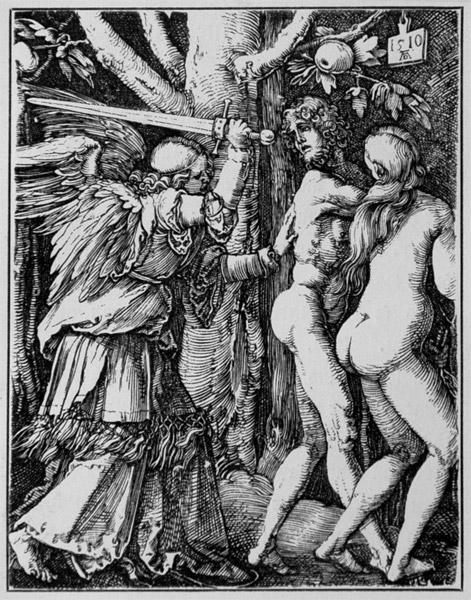

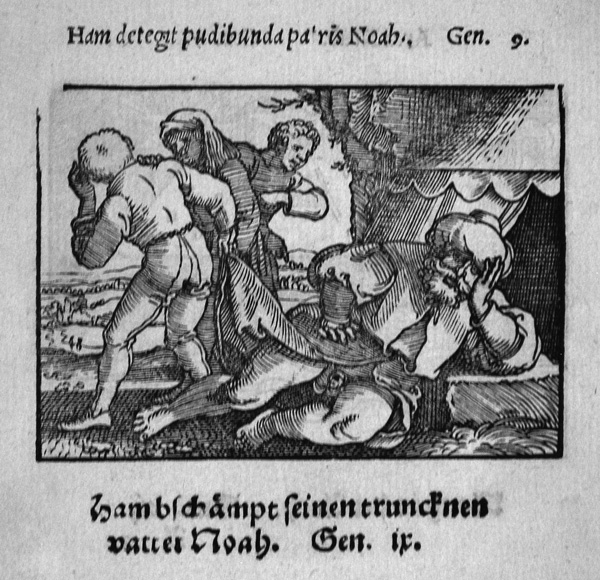

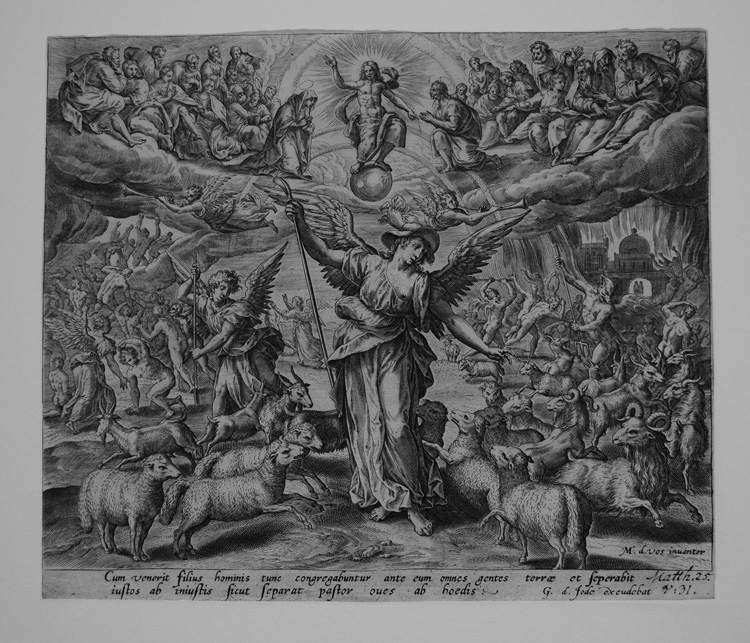

Before the Reformation, the subjects most likely to be depicted in religious art included images of the Virgin Mary (over one third of Italian churches at the end of the 15th century had at least one image of the Virgin and child with or without saintly companions), devotional images of saints commissioned for altar pieces, devotional works for side chapels in churches, events from the life of Jesus, specific local miracles, and images from the Old Testament beginning with Adam and Eve's fall in the Garden of Eden. With the explosive growth in the production of prints, opportunities to create images abounded and the audience for them multiplied: now even those much lower down on the financial tree could own their own art and with the Reformation, doctrinal issues seem to have become central for many commissioning and publishing prints. Prints could depict individuals who were either positive or negative examples and prints could depict biblical histories by showing cycles devoted to significant biblical events like creation, temptation, fall, the life of fallen man, heroes and heroines of the Old and New Testaments, and subjects from the life of Christ, usually focusing on his miracles or his sufferings, and images showing the acts and sufferings of the faithful.

In the North, the centers of artistic activity in the early part of the century were focused in Nuremberg, where Albrecht Durer and the artists he influenced (like Hans Sebald Beham, Heinrich Aldegrever, Georg Pencz, Daniel and Hieronymous Hopfer, and others) worked; and in the Netherlands, where Lucas van Leyden's works were a starting point for those who came after. As Netherlandish artists started traveling to Italy and returning with a whole new set of ideas about how prints ought to look and work, Mannerism based upon Italian models (especially Raphael, Michelangelo, and Titian) but drawing as well upon the works of Durer and Lucas became the dominant style and the lands that would become Belgium and Holland became the center of the print world. During the mid to late 16th century and the fiirst part of the 17th century, artists and print publishers located in Antwerp (like Cornelis Cort, Jan Sadeler, Phillip Galle, the Wierix brothers, the Collaert brothers) or, after the fall of Antwerp to the Spanish, in other Dutch cities (including artists like Hendrick Goltzius or Rembrandt) produced large bodies of work published in books, in portfolios, and as single sheets for large publishers like Hieronymous Cock or the Plantin-Moretus publishing dynasty.

Within this large body of images, we have chosen to present several groups as identified above and several overviews. The two sets of prints depicting the heroines of the Old Testament and of the New by Adrien and Hans Collaert and by Carel de Mallery after drawings by Maerten de Vos (see links above) provide an easy introduction to the question of the role of individuals in 16th- and early 17th-century art; the links to specirfic individuals like Adam and Eve, Lot and his daughters, Samson and Delilah, Judith, Susanna, Jephthah and his Daughter, the Virgin, and Mary Magdalene among others provide extended glimpses of some different kinds of presentations of these key figures suggesting that Renaissance artists and viewers may have been both more complex and more spohisticated in their presentations than they have recently been given credit.