|

|

After the Spanish victory in the southern provinces of what used to be Burgundy during the civil wars / rebellion of the late 16th century and the early 17th century, the Jesuits began building churches and commissioning art in an attempt to confirm the faith of Catholics living in what would later become Belgium and to overwhelm the senses of Protestants so that they might be the more easily converted to Catholicism. One of the chief instruments in this program was the Flemish painter, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), the most renowned northern European artist of his day, and now widely recognized as one of the foremost painters in Western art history. By completing the fusion of the realistic tradition of Flemish painting with the imaginative freedom and classical themes of Italian Renaissance painting, he fundamentally revitalized and redirected northern European painting.

Rubens's upbringing mirrored the intense religious strife of his age--a fact that was to be of crucial importance in his artistic career. His father, an ardently Calvinist Antwerp lawyer, fled in 1568 to Germany to escape religious persecution, but after his death (1587) the family moved back to Antwerp, where Peter Paul was raised a Roman Catholic and received his early training as an artist and a courtier. By the age of 21 he was a master painter whose aesthetic and religious outlook led him to look to Italy as the place to complete his education. Upon arriving (1600) in Venice, he fell under the spell of the radiant color and majestic forms of Titian, whose work had a formative influence on Rubens's mature style. During Rubens's eight years (1600-08) as court painter to the duke of Mantua, he assimilated the lessons of the other Italian Renaissance masters and made (1603) a journey to Spain that had a profound impact on the development of Spanish baroque art. He also spent a considerable amount of time in Rome, where he painted altarpieces for the churches of Santa Croce di Gerusalemme (1602; now in Hopital du Petit-Paris, Grasse, France) and the Chiesa Nuova (1607; now in Musee de Peinture et Sculpture, Grenoble, France), his first widely acknowledged masterpieces. His reputation established, Rubens returned to Antwerp in 1608 following the death of his mother and quickly became the dominant artistic figure in the Spanish Netherlands.

Studies by Michael Jaffe and Jeremy Wood have shown the impact of Italian art on Rubens' development. While in Italy, Rubens bought many drawings and, according to Wood, he drew upon them for the rest of his artistic life, revising and redrawing the prints and drawings he purchased in Italy and in doing so finding new possibilities for his own art. In the mature phase of his career, Rubens either executed personally or supervised the execution of an enormous body of works that spanned all areas of painting and drawing. A devout Roman Catholic, he imbued his many religious paintings with the emotional tenor of the Counter-Reformation. This aggressively religious stance, along with his deep involvement in public affairs, lent Rubens's work a conservative and public cast that contrasts sharply with the more private and secular paintings of his great Dutch contemporary, Rembrandt. But if his roots lay in Italian classical art and in Roman Catholic dogma, Rubens avoided sterile repetition of academic forms by injecting into his works a lusty exuberance and almost frenetic energy. Glowing color and light that flickers across limbs and draperies infuse spiraling compositions such as The Descent from the Cross (1611; Antwerp Cathedral) with a characteristically baroque sense of movement and tactile strength.

A love of monumental forms and dynamic effects is most readily apparent in the vast decorative schemes he executed in the 1620s, including the famous 21-painting cycle (1622-25; Louvre, Paris), chronicling the life of Marie de Medici, originally painted for the Luxembourg Palace. In order to complete these huge commissions, Rubens set up a studio along the lines of Italian painters' workshops, in which fully qualified artists executed paintings from the master's sketches. Rubens's personal contribution to the over 2,000 works produced by this studio varied considerably from work to work. Among his most famous assistants were Anthony van Dyck and Frans Snyders.

Rubens's phenomenal productivity was interrupted from time to time by diplomatic duties given him by his royal patrons, Archduke Ferdinand and Archduchess Isabella, for whom he conducted (1625) negotiations aimed at ending the war between the Spanish Netherlands and the Dutch Republic and helped conclude (1629-30) a peace treaty between England and Spain. Charles I of England was so impressed with Rubens's efforts that he knighted the Flemish painter and commissioned his only surviving ceiling painting, The Allegory of War and Peace (1629; Banqueting House, Whitehall Palace, London).

During the final decade of his life, Rubens turned more and more to portraits, genre scenes, and landscapes. These later works, such as Landscape with the Chateau of Steen (1636; National Gallery, London), lack the turbulent drama of his earlier paintings but reflect a masterful command of detail and an unflagging technical skill. Despite recurring attacks of arthritis, he remained an unusually prolific artist throughout his last years, which were spent largely at his estate, Chateau de Steen [Much of the above is taken from The Web Museum, Paris].

The bibliography on Rubens is immense. For starters see Ronni Baer, So Many Brilliant Talents: Art and Craft in the Age of Rubens (Emory: Carlos Museum, 2000); Frans Baudouin, Peter Paul Rubens, trans. Elsie Callander (NY: Portland House, 1977); Kristin Lohse Belkin, Rubens (London: Phaidon Press, 1998); Julius S. Held, Rubens and His Circle, ed. Anne W. Lowenthal, David Rosand, & John Walsh, Jr. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982); Julius S. Held, Rubens: Selected Drawings With an Introduction and a Critical Catalogue by Julius S. Held. 2 vols. (London: Phaidon Press, 1959; revised edition 1986); Michael Jaffé, Rubens and Italy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977); Anne-Marie Logan, Flemish Drawing in the Age of Rubens: Selected Works from American Collections (Wellesley: Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, 1993); Anne-Marie Logan and Michael C. Plomp, Peter Paul Rubens: The Drawings (NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005); The Letters of Peter Paul Rubens, trans. and ed. Magurn and Ruth Saunders (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1991); Felice Stampfle, Rubens & Rembrandt in Their Century: Flemish & Dutch Drawings of the 17th Century in the Pierpont Morgon Library (NY: Pierpont Morgon Library, 1979); Catherine Whistler & Jeremy Wood, Rubens in Oxford (Oxford: The Picture Gallery, Christ Church, 1988); Jeremy Wood, Rubens: Drawing on Italy (Edinburgh: National Gallery of Scotland, 2002). Still in progress: The Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard in 26 parts.

|

|

|

|

|

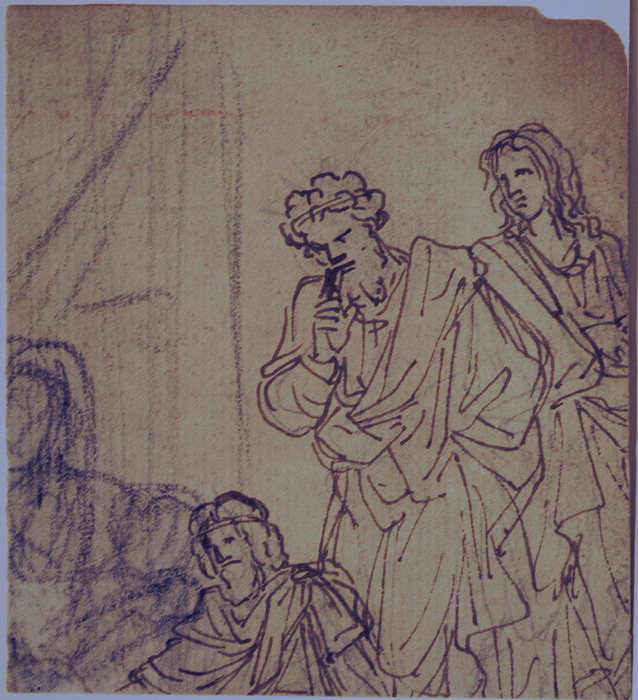

This is the cancelled draft of a letter written on the reverse of the St. Francis above:

"Nota de’ travaglij fatti da’ me per servizio di Sua Ma.a per ordine del’Illsmo Sig. Intendente Generale De Gregori

Per haver dipinto diversi Gruppi Historiani di fighure in quattro lavozze tre per il seguito di Sua Ma la Regina et l’altra per servizio si Sua Al.a Sevea la Sig.a Prinsipessa Des le quali in tutto compongono quattro panelli grandi due…"

"Note of the jobs I did to serve His Majesty at the order of General Superintendent De Gregori

For having painted various groups of historical figures in four works, three for the series of Her Majesty the Queen and the other as a service for her highness the Princess that taken together compose four very large decorative panels …"

The most likely candidate for a Queen who was ordering works for her series of paintings would be Marie de' Medicis, dowager Queen of France, for whom Rubens executed a long series paintings on her life (now in the Louvre) and with whom he had been negotiating for a second series of works in the 1620s on the Life of Henri IV (assassinated 1610; the King would then be Louis XIII, who finally exiled his mother in 1630; and the most likely date for the letter would be before the completion of the series of twenty-four paintings for the Life in 1625. Marie had three daughters, Elisabeth, Queen of Spain (married Philip IV in 1614); Henrietta Maria, who married Charles I in 1625 and became Queen of England; and Christine Marie, who married the Duke of Savoy in 1619, becoming Duchess of Savoy and who wold have had the rank of a Princess.

If the letter is indeed in Rubens' hand (his correspondance was normally written in Italian and the hand-writing seems similar to that in a letter he wrote in 1618 reproduced in C. V. Wedgewood, The Political Career of Peter Paul Rubens (London: Thames annd Hudson, 1975), p. 32, the likelihood that this is by Rubens is indeed very, very high. Hans Vlieghe, The Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard Part VIII: Saints, 2 Parts (London: Phaidon, 1972) inventories Rubens' paintings and drawings of St. Francis receiving the Stigmata, none of which clearly relate to our drawing, as catalogue numbers 90, 90a, 90b, 9a, 91a, 92, and 93, and illustrates them as figures 154-61.

|

|

|