|

|

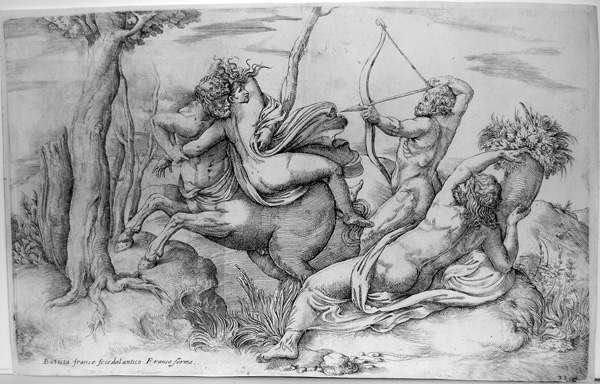

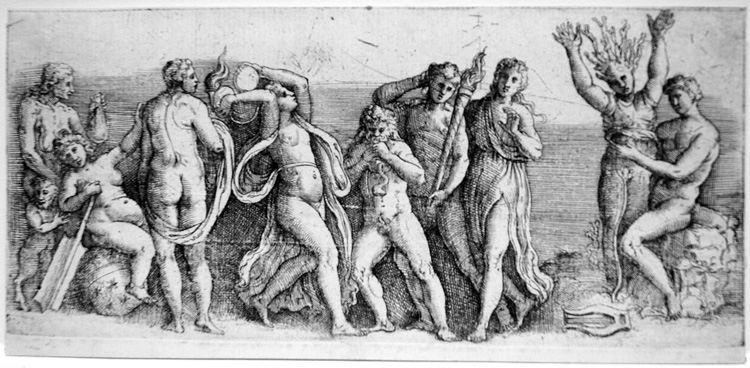

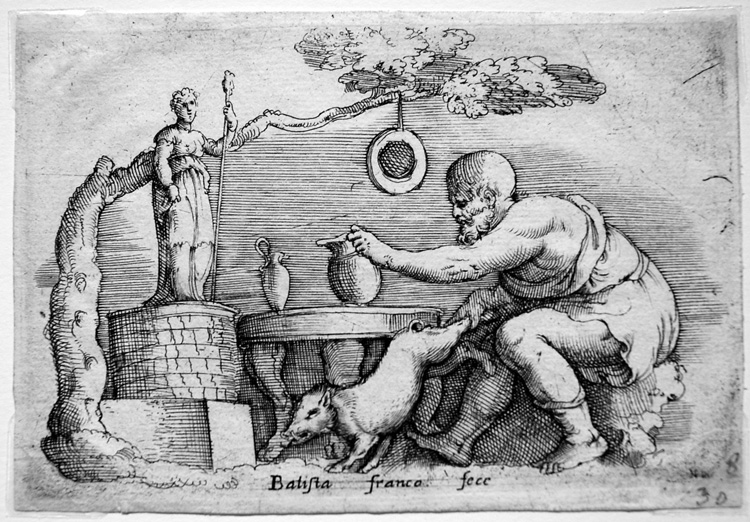

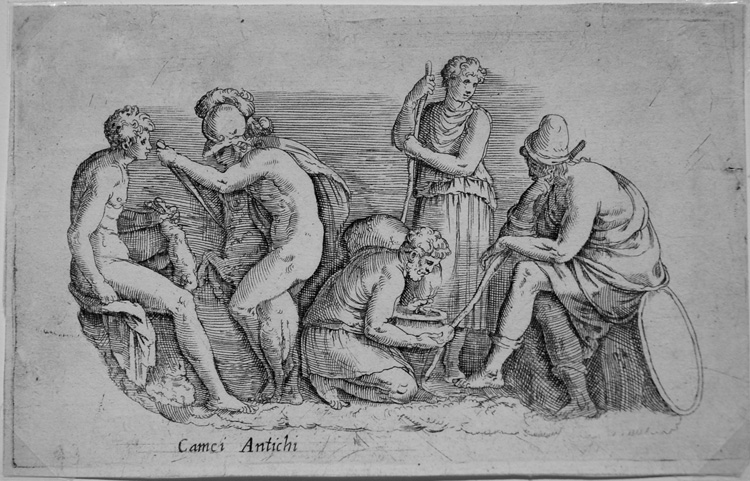

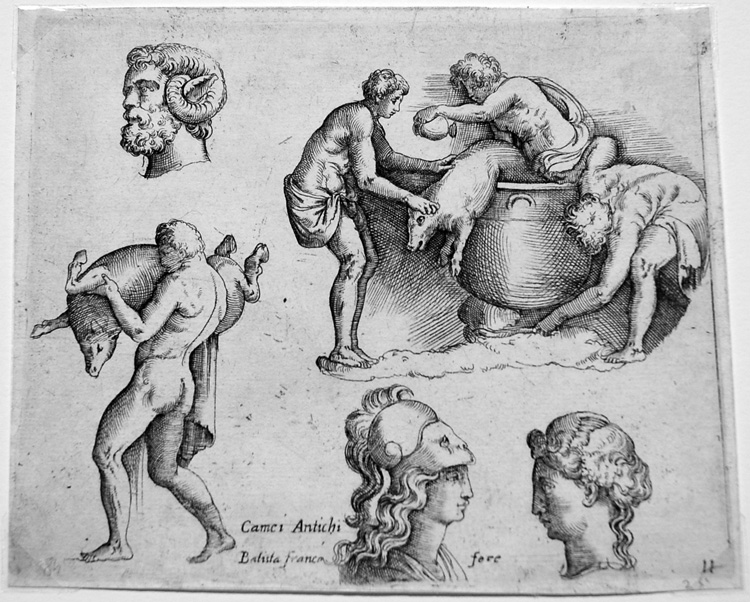

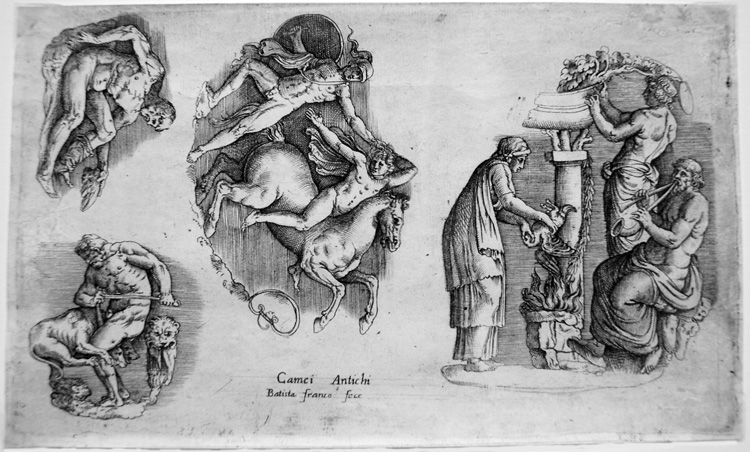

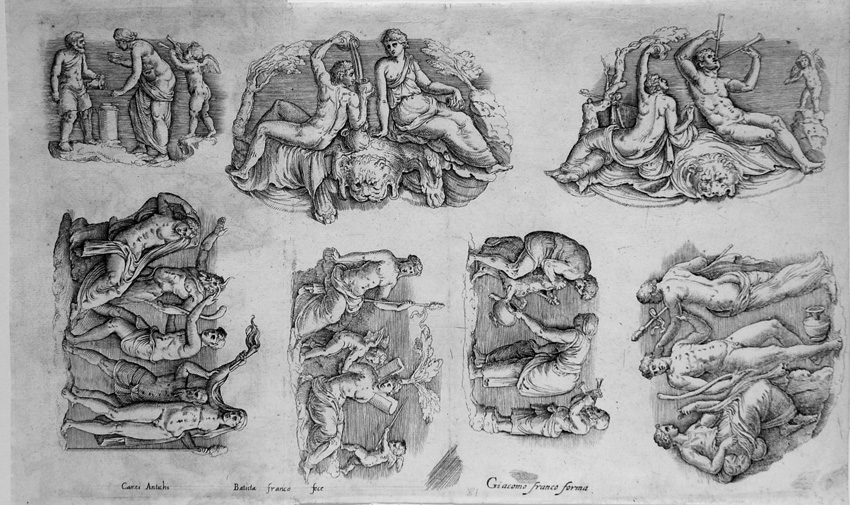

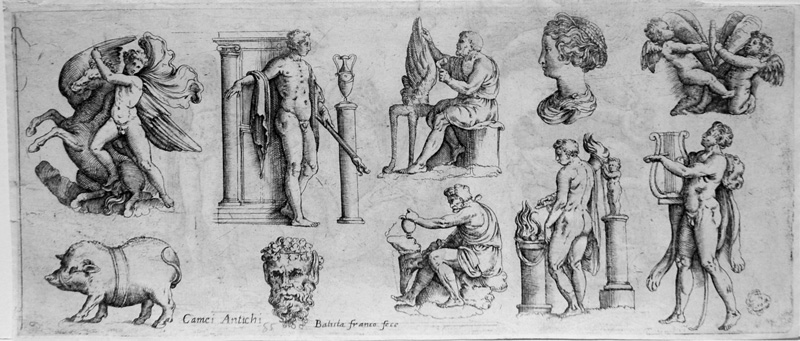

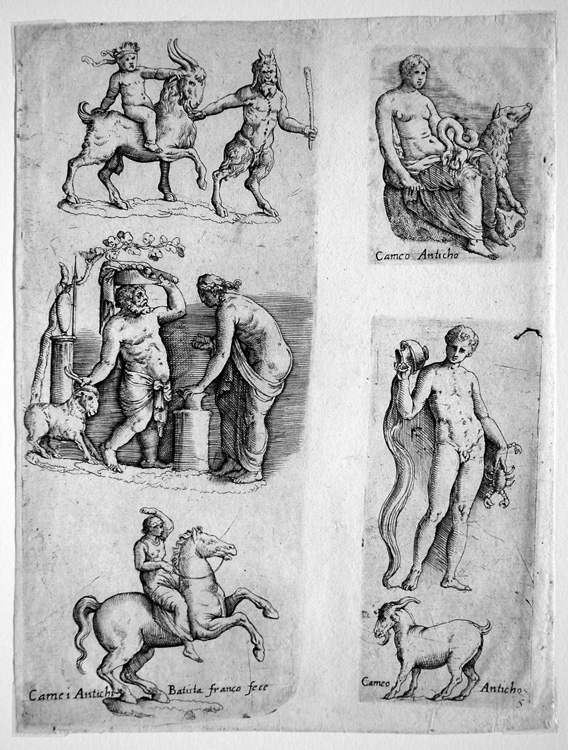

Giovanni Battista Franco (before 1510 - 1561, also know as Battista Franco Veneziano) was an Italian Mannerist painter and printmaker in etching active in Rome, Urbino, and Venice in the mid 1500s. He is also known as il Semolei or just Battista Franco (as he often signed himself in his prints). Native to Venice, he came to Rome in his twenties. He painted an allegory of the Battle of Montemurlo now in the Pitti Palace (1537), and a fresco of the Arrest of John the Baptist for the Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato (1541). From 1545-51 he painted in Urbino. He may have been, along with Girolamo Genga, one of the mentors of Federico Barocci. He studied in Rome, giving special attention to the works of Michelangelo, and took great interest in designing allegorical decorations on a large scale. He worked with Vasari in carrying out some decorative work in a palace for Ottaviano de' Medici, but is better known for his portraits of the Medici family, which were, however, to a great extent copies from the works of other men. His designs for majolica were of importance and were executed for the Duke of Urbino; but perhaps he is better remembered for his etchings, of which there are over a hundred, than for any other works. He returned to Venice, where he helped fresco the ceiling of the Biblioteca Marciana (library). He painted a series of panels, including a Baptism of Christ, for the walls and vault of the Grimani chapel in the church San Francesco della Vigna in Venice. He painted the Raising of Lazarus in the Ducal palace. (For the bare facts of his career, I am indebted to entries in Wikipedia and The Catholic Encyclopedia; for a more complete outline, see Maria Sica's entry in the Grove Dictionary of Art, 11: 720-722).)

The first life of Franco was done by Vasari, Battista Franco, Painter of Venice (1498-1561), vol. 4, 15-23, who knew him and should have been sympathetic to him for his love of Michelangelo and his obsession with disegno (drawing/design), since those are the very things that Vasari praises elsewhere, especially in his Lives of Michelangelo and Titian. His Life of Franco opens as follows: "Battista Franco, having studied design in his early childhood, went at the age of twenty to Rome, where, after having devoted himself to various styles for some time, he resolved to imitate nothing but the designs, paintings, and sculptures of Michelangelo. Accordingly there was nothing of that master which he did not copy, and before long he became one of the first draughtsmen frequenting Michelagnolo's chapel, and for some time he did nothing but draw without caring to paint" (p. 13). After praising his first commission for a series of paintings depicting the battles of the Scipios father and son against Carthage, in which he notes that these were his first paintings in colors ("Although he had never touched colors . . . all of these scenes were of considerable merit and much praised as being Battista's earliest works and by comparison with those of the others," he then critiques him: "If he had first begun to paint and learned the use of colors and the brush he would have doubtless surpassed several of the competitors, but he persisted in an opinion held by many, that a painter need only know drawing, to his great prejudice" [IV, 16]. When Franco does one of the ten large paintings commissioned for the marriage of Duke Cosimo de' Medici with Leonora of Toledo, Vasari (who notes that he himself had absented himself from the felicity, "determined never to follow courts again, for he had lost his first master, Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici and then Duke Alessandro" [IV, 17]), says of Franco, "The best thing he did for the wedding was one of the ten pictures of the great court of the Medici palace, representing Duke Cosimo in grisaille. . . . But in spite of his diligence he was surpassed by Bronzino and the others, who were inferior to him in design but who excelled him in invention, vigor, and the treatment of grisaille, for, as I have elsewhere remarked, paintings must be executed with ease and the things disposed with judgment, too much effort making them appear hard and crude. Too great a strain often spoils a work, destroying the facility, grace, and vigor which are usually natural gifts, though they may to a great extent be acquired by study and art" (IV, 17-18).

Perhaps having felt that he had gone too far, for the remainder of his Life of Franco, Vasari tries to find things he can praise about Battista's works. So, when Vasari comes to the Duke of Urbino to make his excuses for not having answered a call to paint works for his wedding, he praises Franco's works: "the Duke showed him the chapel painted by Battista, wishing to hear his opinion. Vasari praised it greatly and extolled the ability of the artist, who was liberally rewarded by the duke" (IV, 21). Ultimately, Vasari's position seems to be that in the making of designs, whether for vases [IV, 20] or engravings [IV, 23], Battista Franco "had no peer" [IV, 20] and "his numerous printed designs, which are truly admirable, have given him a great reputation" [IV, 23]. I think that part of Vasari's problem with Franco may be that since Franco and Vasari himself were often competing for the same commissions, Vasari wants to make sure that it be known that Franco is more wedded to older styles, and that great painting "requires grace and charm" (IV, 19], "vivacious and graceful heads" (IV, 19], "executed with ease and the things disposed with judgment, too much effort making them appear hard and crude." [IV, 18]. Himself one of the embodiments of the "stylish style" of Mannerism, Vasari finds Franco's attempts to continue on the heroic vein of Michelangelo's peerless frescoes in the Vatican too threatening professionally, a notion reinforced in his remarks about Tintoretto, whose life is also included in the Life of Battista Franco (IV, 23-26), who would seem to embody all the positive qualities that Vasari finds lacking in Franco, but whom he criticizes because Tintoretto lacks "design and judgment" [IV, 23] even though he "possessed the most stupendous brain that painting has ever known, as we see in all his works and compositions, which differ widely from those of other artists, and he surpassed himself with new and extraordinary inventions, the creations of his intellect, and worked at hazard, without design, as if to show that this art is a trifle. He sometimes left his finished sketches so gross that the pencil-strokes possess more vigor than design and judgment, and seem to have been made by chance" [IV, 23]. Neither design and judgment nor "extraordinary invention" [IV, 23] and facility and speed of execution are enough for greatness, and Vasari faults Franco and Tintoretto for each lacking what the other possesses in abundance.

In his text for Mannerist Prints: International Style in the 16th Century (LA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988), Bruce Davis calls Franco "one of the finest Italian printmakers of the midsixteenth century" and calls for "further study" (p. 328) and now there is, as of 2007, a monographic study of Franco, whose prints are being included in major exhibitions of Sixteenth Century Italian printmaking, itself a much neglected field. Davis complicates Vasari's picture of a single-minded disciple of Michelangelo by noting that Franco has also studied the works of Giulio Romano and Giulio Bonasone and that in the late 1540s, when he was near Mantua, where Giulio Romano was the court artist, Franco etched 4 prints after his designs (p. 83)

Selected Bibliography: For a complete illustrated catalogue of Franco's etchings, see Henri Zerner, The Illustrated Bartsch 32: Italian Artists of the Sixteenth Century School of Fontainebleau (NY: Abaris Books, 1979), pages 156-258; Fabrizio Biferali & Massimo Firpo, Battista Franco "pittore viniziano" nella cultura artistica e nella vita religiosa del Cinquecento (Pisa: Ediziioni della Normale, 2007); Bruce Davis, Mannerist Prints: International Style in the 16th Century (LA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988); Gianvittorio Dillon, "Le incisioni" in Da Tiziano a El Greco. Per la storia del Manierismo a Venezia, 1540-1590 (an exhibition catalogue accompanying a show at the Palazzo Ducale in Venice (Milan: Electra Editrice, 1981), pages 314-318, nos. 142-77; Sue Walsh Reed and Richard Wallace, Italian Etchers of the Renaissance & Baroque (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1989), pages 53-57, nos. 25-27; Lucia Fornari Schianchi, ed. Parmigianino e Il Manierismo Europeo: Atti Del Convegno Internazionale Di Studi Parma,13-15 Giugno 2002 (Milano: Silvana Editoriale, 2002 ); John Shearman, Mannerism (NY: Penguin, 1967, 1973); Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, 4 vols (London: Everyman's Library, 1963; Vasari's life of Franco can be found in vol. 4, pages 15-23).

|

|

|

|

|