|

Welcome to Spaightwood Galleries, Inc.

120 Main Street, Upton MA 01568-6193

You can follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

We blog regularly on Facebook and announce special events and special sales on both sites.

Last updated: 7/21/2017

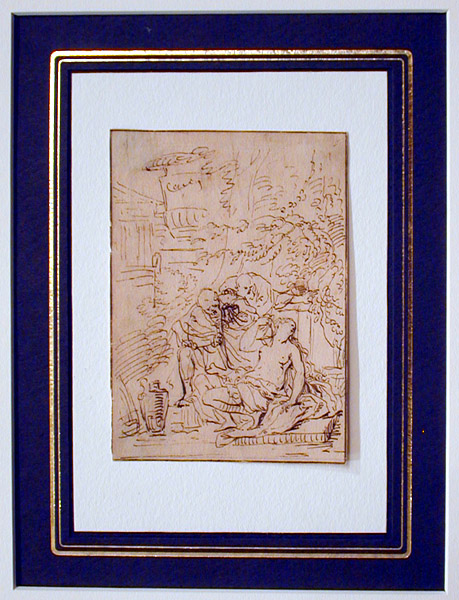

Old Master Drawings: Bernaert van Orley (Netherlandish, 1492-1542)

|

|

|

|

Van Orley is an important Netherlandish master whose works are in the collections of most major national museums, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, London, and Edinburgh, the British Museum, the Louvre, the Musée des Beaux Arts in Brussels, the Antwerp Museum, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Prado in Madrid, museums in Turin, Oslo, Budapest, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Mew York, and the Worcester Museum of Art in Massachusetts (about 20 miles from Upton). Van Orley was the court painter to the Hapsburg regents Margaret of Austria and her successor, Mary of Hungary, in Brussels, and when Dürer visited Brussels during his trip to the Netherlands in 1520, he stayed with van Orley and did a portrait of him. Michael C. Plomp, writing in the Fall 2003 Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin notes that "Van Orley was the first designer of tapestries and stained glass windows whose work showed an informed response to the aesthetics of the Renaissance."Arlette Calvet has suggested that "Van Orley's talents were no doubt most fully expressed in his cartoons for tapestries, where his art achieves an almost classic breadth and ease. Among those belonging to the Louvre, the most significant may be the twelve small cartoons . . . connected with the famous hangings representing Maximilian's Hunts. . . . Van Orley displays exceptional creative talent in his conjured scenes of imaginary hunts; for the artists coming after him, he opened up new paths to Italianism, thereby transforming the conception of the landscape, which he rendered with remarkable truth and spontaneity." Roseline Bacou, Great Drawings of the Louvre: The German, Flemish and Dutch Drawings (N.Y.: Braziller, 1968), commentary on plate 39.

The story of Susanna is told in the Apocryphal Book of Daniel and Susanna. Susanna, brought up by religious parents who taught her the law of Moses, married Joakim, a very rich man of Babylon at whose house the elders of the Jews met and where they held their trials. Joakin had a walled garden at this house and it was to this garden that his beautiful wife would resort when the elders came. The incident that follows shows the truth of the Lord's saying, "Wickedness came forth from Babylon, from the elders who were judges and who were supposed to govern the people" (1:5-6). Two of the judges became obsessed with Susanna because of her beauty and lusted after her. Although each was too ashamed to tell the other of his feelings, one day, after each left Joakim's house they each sneaked back to spy on Susanna and discovered their mutual lust. Resolving to seek an opportune time, they kept a close eye on Susanna and waited for a chance to catch her alone. One very hot day, Susanna and her two maids went into the garden and Susanna decided to take a bath. She sent her two maids out for soap and olive oil and bade them to lock the gates until their return. The two elders, who were already inside the garden, ran up and demanded that Susanna yield to them: "'If you refuse, we shall give evidence against you that there was a young man with you and that was why you sent your maids away.' Susanna groaned and said, 'I see no way out. If I do this thing the penalty is death; if I do not, you will have me at your mercy. My choice is made: I will not do it. It is better to be at your mercy than to sin against the Lord'" (1:21-23). The elders promptly shouted down her cries for help and accused her, shocking everyone, for her reputation was spotless. The two elders proclaimed their story and demanded her death. Susanna "looked up to heaven through her tears, for she trusted in the Lord." The people believed the judges and assented to her death, but as she was being led away, affirming her innocence and appealing to God, "who dost know all secrets and foresee all things, thou knowest that their evidence was false" (I: 42-43), the young Daniel is inspired by the Lord to come to Susanna's aid. The rest of the elders accept his authority, seeing that "God has given you the standing of an elder" (I: 50), and Daniel proceeds to have the elders separated and questions them about the details of their story. When they disagree, he proclaims their crime and the people turn upon them, "for out of their own mouths Daniel had convicted them of giving false evidence" (I: 61) and they are stoned to death according to the law of Moses.

Besides giving artists a chance to show a beautiful woman without any clothes on, the story also gives artists a chance to show the faith of Susanna and her trust that God will save her, the depravity of those who wold use the law for their own personal profit, and perhaps also to draw a comparison between Susanna and Lucrece who, in a similar situation, did not resist in the face of Tarquin's threat to kill her and a servant and tell everyone that she was taken in the act of adultery, leaving no one alive to tell her story and prevent her reputation and that of her husband from being stained. By following the biblical text and showing Susanna naked, artists might also be inviting viewers to see that like the two corrupt judges, who made Susanna unveil herself at her trial "so that they might feast their eyes upon her beauty" (I: 32), they too were not immune from this hunger. For other Renaissance depictions of this story, see our web page devoted to the story of Susanna and the Elders . Bernaert van Orley's drawing of the two lecherous old men who try to blackmail a beautiful young woman into having sex with them is one of the earliest versions of this story, which became quite popular in the Netherlands in the Renaissance.

Bibliography: Maryan Wynn Ainsworth, "Bernart van Orley, Peintre-Inventeur," in Studies in the History of Art, Volume 24 (Washington D. C.: National Gallery of Art, 1990), Brou, Musee de l'Ain. Van Orley et les Artistes de la Cour de Marguerite d'Autriche (Brou: Musee de l'Ain, 1981); Bruxelles, Societe Royale d'Archeologie de Belgique. Bernard van Orley 1488-1541 (Bruxelles: Societe Royale d'Archeologie de Belgique, 1943); Marthe Crick-Kuntziger, La Tenture de l'Histoire de Jacob d'apres Bernard Van Orley (Antwerp, 1954); J. David Farmer, "How One Workshop Worked: Bernard van Orley's Atelier in Early Sixteenth-Century Brussels," A Tribute to Robert A. Koch: Studies in the Northern Renaissance (Princeton: Department of Art and Archaeology, 1994), 21-51; Max Friedlander, Early Netherlandish Painting, vol. VIII: Jan Gossart and Bernart van Orley trans. Heinz Norden (NY: Praeger, 1972); Lode Seghers, Bernard van Orley: Apocalypse (Antwerpen: Lode Seghers, 1956).

|

|

|