|

Giovanni Francesco Barberi was nicknamed Guercino because he was "guercio," or cross-eyed. Born in poverty in Cento, near Ferrara, he was largely self-taught, though he also served a brief apprenticeship. The glowing colorism and emotion of Lodovico Carracci's Holy Family with Saint Francis in Bologna influenced him profoundly, and Lodovico himself encouraged the young man. From 1614 to 1621, the year Pope Gregory XV summoned him to Rome, Guercino painted the altarpieces that are his most Baroque creations. With Lodovico's and Caravaggio's works pointing the way, Guercino brought the viewer into the painting's space, adding dramatic lights and darks and greater emotional intensity. Throughout his career, Guercino's style underwent dramatic changes. In Rome he first felt pressured to paint in the popular classicizing style. Returning to Cento two years later, his dark shadows faded, strong movement disappeared, and details emerged distinctly in clear light. To "satisfy as well as he could most of the people, especially those who asked for paintings and had the money to pay for them, he had shown paintings in the lighter style," reported his first biographer. Guercino ran his Cento studio until 1642, when Guido Reni, who had loathed him, died. Guercino then moved to Bologna, taking over Reni's religious picture workshop and his role as the city's leading painter (Source: Getty Museum biography). Stone, Guercino: Master Draftsman, points our that "Drawings played an essential role in . . . [Guercino's] stylistic development and professional career. . . . Like Picasso, Guercino's mind and hand were never idle. He lived to draw. . . . Though the vast majority of his drawings served utilitarian purposes–mainly the preparation of paintings—no other artist of the period made so many sheets for his own delight and the enjoyment of others. Guercino was truly a pioneer in treating drawings as independent works of art. The extraordinary survival of so many of his sheets may have been partly due to the fact that he (and later his heirs) regarded them as a record of his genius and creativity and not merely as the by-product s of painting and fresco projects" (p. xix).

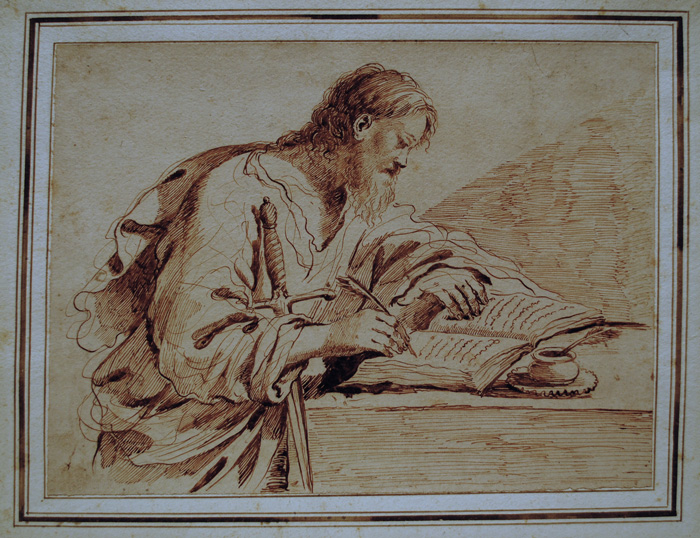

Diane de Grazia's characterization of the qualities that have made Guercino's drawings appealing in his own times and in ours bears repeating: "Even in his own day, the artist was admired for his vibrant and calligraphic pen sketches. He often made quick notations of forms to be used as studies for paintings or merely for his own pleasure. . . . Guercino must have been an indefatigable draughtsman, for after three centuries, what remains of his drawings is found in collections all over the world. His draughtsmanship, with its energetic flashes of the pen, has been much copied but never equalled" (Guercino Drawings in the Art Museum, Princeton University, Introduction). Nicholas Turner and Carol Plazzotta print a series of studies for an "Atlas standing" (figures 144-148, pages 173-178) in which we see Guercino thinking with his pen, changing the direction in which Atlas faces, the angle of his upraised arms, and the orientation of his face, a convincing demonstration that Guercino discovered his subjects as he drew them, like Michelangelo freeing his sculptures from the stone that imprisoned them. Stone, Guercino: Master Draftsman, similarly suggests that most of Guercino's drawings should not be thought of as " 'blueprints' for the style of the paintings they study" but rather that they serve as "intellectual 'time-outs' in which the artist gives himself the freedom to invent, to delve into the istoria, without having to worry about such tedious issues as the size of the canvas, the number of figures he must eventually squeeze into the composition, or even the format of the picture, whether horizontal or vertical" (xxiii). Stone also suggests that the medium for the drawings was often based upon the need to use a technique that offered the most freedom and flexibility in putting images seen by the mind's eye onto the page, noting that Guercino's "preferred drawing medium throughout his life was pen or pen and wash" and his drawings show "the velocity with which Guercino could use his pen to 'attack' his subject on the sheet: the quick succession of pentimenti in the drawing would have been difficult if not impossible to realize in any other medium" (p. xix). Stone points out that Guercino frequently used red chalk "in the middle and later stages of the design process when, for example, it would become necessary to go beyond the mere blocking out of forms conceived in earlier compositional pen studies and he had to begin planning the actual, detailed look of anatomies and draperies. It was often in red-chalk drawings that modelling according to a specific angle of illumination was first considered with any real precision." Stone also notes that "in the later 1640s and 1650s . . . red chalk–which so perfectly predicted the abstraction and delicate pastel tonalities of his paintings–became Guercino's medium of choice" (p. xix).

Bibliography: Alberto Alberghini, Guercino: La Collezione di Stampe (Ferrara, Cento, 1991); Diane DeGrazia, Guercino Drawings in the Art Museum, Princeton University (Princeton: the Art Museum, Princeton University, 1969); Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, ed., Il Guercino 1591 - 1666 (Bologna: Nuova Alfa Editoriale, 1991: Catalogue of the Guercino exhibition, held in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna in 1991); Michael Helston and Francis Russell, Guercino in Britain: Paintings from British Collections (London: National Gallery Publications, 1991); Denis Mahon, Il Guercino. Catalogo critico dei disegni a cura di Denis Mahon (Bologna: Alfa, 1968); David M. Stone, Guercino: Master Draftsman (Bologna: Nuova Alfa Editoriale, 1991; the catalog of a travelling show organized by the Harvard University Art Museums); David M. Stone, Guercino: cataloge completo die dipinti (Cantini 1991); Nicholas Turner, Guercino Drawings From Windsor Castle (Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991); Nicholas Turner and Carol Plazzotta, Drawings by Guercino from British collections: with an appendix describing the drawings by Guercino, his school and his followers in the British Museum (London: British Museum Press, 1991).

|

|

|

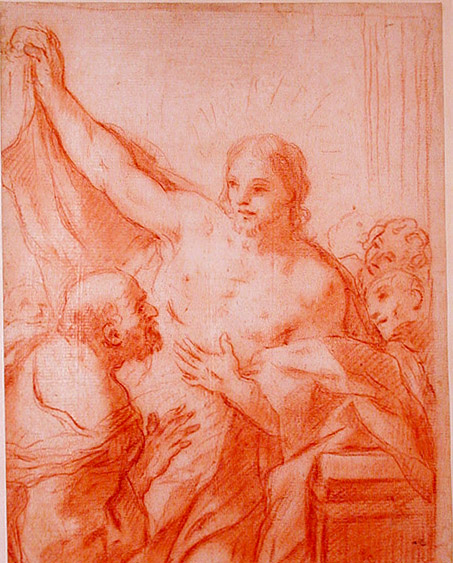

Guercino, attributed, Doubting Thomas. Red chalk drawing on laid paper with no watermark, c. 1621? Stamped with the collector's mark of J. Auldjo (Lugt 48). A previous owner has noted "Guercino" as the author of this drawing, in which St. Peter watches as St. Thomas reaches around from behind to insert his left hand into the wound in Christ's side at Jesus' command so that he might not perish through his unbelief. For a 1621 oil painting of the same subject, see David M. Stone, Guercino: cataloge completo die dipinti n. 73, p. 95 or Stone, Guercino: Master Draftsman, fig. 10a, p. 24, where it is accompanied by one of the preparatory drawings, p. 25. The painting, like our drawing, shows Christ, St. Thomas, St. Peter, and additional disciples (in this case, 2). The drawing in Stone, which differs significantly from the painting, shows only Christ and St. Thomas. Image size: 264x204mm. Price: Please call or email for current pricing information 500.

In July 2010, one of Guercino's paintings sold at Christie's London for Please call or email for current pricing information,240; the high price for one of his drawings at auction is Please call or email for current pricing information (Sotheby's, London, July 2006), and since 1990, 15 of his drawings have sold at auction for over Please call or email for current pricing information.

|

|

|