|

Jules Olitski, who came to the U.S. in 1923 after the execution of his father for political reasons, was an important figure in the "Color field painting" movement. In Cynthia Dantizic's essay in the Grove Dictionary of Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996 and later editions), he is listed as as among a fairly small group of artists who brought this subset of Abstract Expressionist painting to prominence: "such Abstract Expressionists as Barnet Newman, Mark Rothko, and Clifford Still, and . . . subsequent American painters, including Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella, Jules Olitski, and Helen Frankenthaler" (7:636-37; I quote here from p. 636). The term was coined by Clement Greenberg in an important essay, "American-Type Painting," Partisan Review, xxii/2 (1955), 179-196), where Greenberg differentiated between painters like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, for whom the drama often lay in the physicality of the surface of the paint on the canvas, and Olitski, Louis, and Frankenthaler, whose work invited us to learn how to see subtle variations of color and texture. In his paintings during the 1960s and 70s, Olitski often sprayed paint directly on the surface of the canvas, "a method he had experimented with previously and which had become his dominant method by 1965. . . . He elaborated the method over the next few years, varying the number of spray guns and often using brush strokes to create borders in contrasting colors" (Jules Olitski, Grove Dictionary of Art, 1996, 23: 403-; I quote here from p. 404). Widely regarded as one of America’s last classic modern painters, Jules Olitski (1922–2007) created brilliant color harmonies and chromatic shifts that became one of the hallmarks of Color Field painting. Olitski enjoyed enormous acclaim in the 1960s and 1970s: in 1966 he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale and in 1969 he was the first living American artist to be given a solo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A list of his solo exhibitions would take too much space, but it would include galleries and museums in France (1951, 1976, 1980, 1984, 1985), Italy (Florence, Rome, and Milan in 1963, Milan, 1974,), England (1964, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1972, 1975, 1981), Canada (1965, 1966, 1968, 1971, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1989, 1990), Germany (1977, 1978, 1981, 1983), and many others (my list of shows only goes up to 1990). His works have been shown in museums in the U.S., Canada, Italy, West Germany (Documenta IV), Japan (9th Tokyo Biennial),W. Germany, and others. His works are in the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, The MFA (Boston), Princeton University, M.I.T., Milwaukee Art Center, the Dallas Museum of Fine Art, The Fogg Art Gallery (Harvard), the Chicago Art Institute, the Smart Gallery of the University of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, The Rose Art Museum (Brandeis), the Corcoran Gallery of Art (D.C.), Guggenheim Museum, Brooklyn Museum, Dayton Art Institute, Albright-Knox Art Gallery (Buffalo), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts (Houston), U. Michigan Museum of Art, Nelson-Atkins Museum (Kansas City), The Israel Museum (Jerusalem), The Tel-Aviv Museum, Australian National Gallery, the Art Collection of Nordheim-Westfalen, (Dusseldorf), the Edmonton Art Gallery in Alberta Canada, the Musée de Lyon (in France), the St. Louis Art Museum, Yale University Art Gallery, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and many others. He was also commissioned to make three large screenprints for Lincoln Center in NYCity, for which see Olitski2.

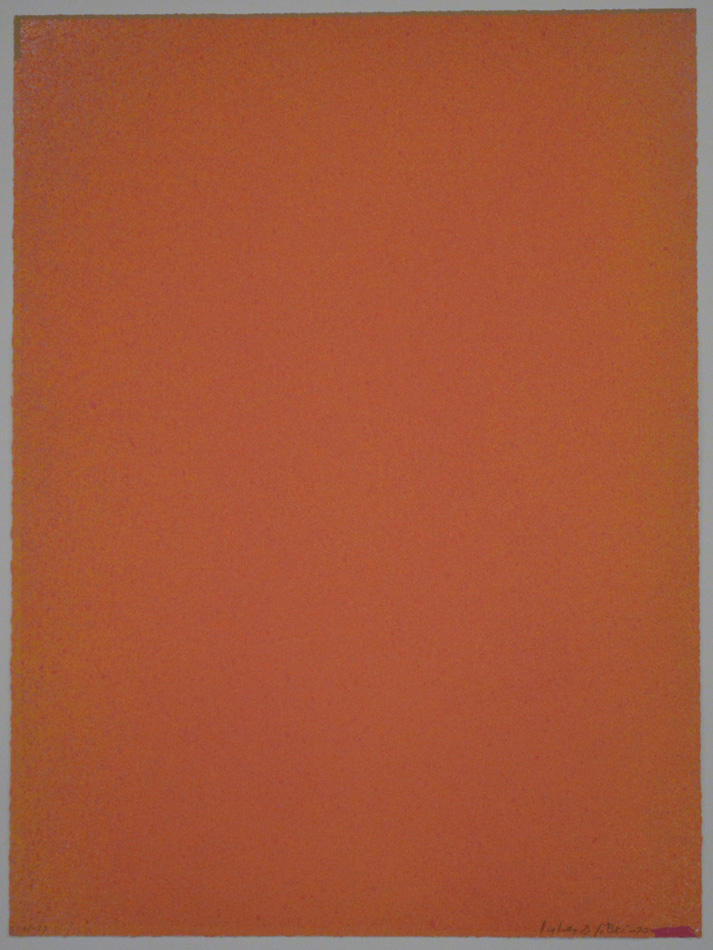

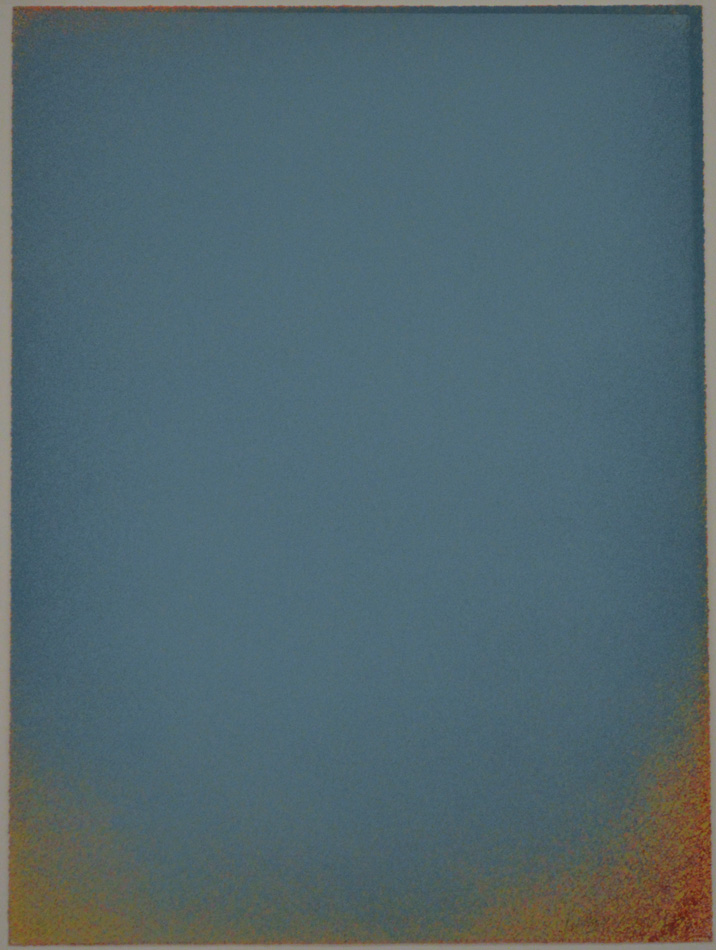

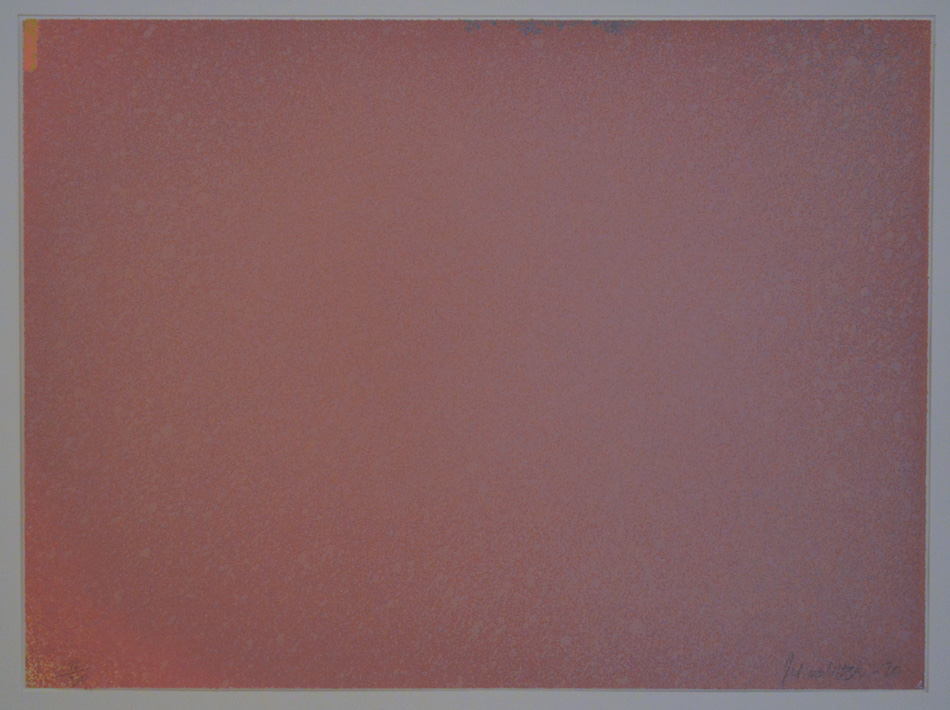

As Karen Wilkin observed in The Prints of Jules Olitski: A Catalogue Raisonné 1954-1989, the same artistic aims are fulfilled in his prints beginning in the 1970s: "The colored silkscreens of the early 1970s . . . are evidence that Olitski could also approach printmaking very much as he did painting. Like the canvases of the period, the silkscreens are more or less unbroken expanses of saturated high key color. Like the paintings, too, the silkscreens are punctuated by incidents confined to the edges. There, however, the resemblance ends. We perceive the silkscreen quite differently than we do the paintings. In part this is due to the prints' intimate scale [(35x26 inches or 26x35 inches (890x660mm or 660x890mm)], which pulls us close to them. From this vantage point, their layers of superimposed radiant color become fairly apparent. (From further away, these colors tend to mix optically, as in Impressionist painting, to create fugitive pulsating hues.) The sense of built-up surface that results from the necessity of using many screens to carry separate, divided colors in order to make a delicately modulated expanse is a precise equivalent for what Olitski achieved in his paintings of the 1970s with layers of coarse spray, but our relationship to the surface of the prints is more intimate; the large paintings keep us at a distance, so we are not immediately aware of the particulars of surface. Rather, we are confronted by an overwhelming expanse of color" (p. 13).

Unlike commercial screenprints, which tend to be based upon photographs, an artist’s screenprint or serigraph (for want of a better term) is not a mass-produced photographic reproduction: each color is hand-printed in a separate press run. The screens can be hand-painted, stenciled on, or an image can be laid on the screen photographically. Once the screens are done, ink is forced through the screens onto the paper using a squeegee or vacuum press (for glopping lots of ink through; screenprints by Sam Gilliam or Bill Weege produced on Weege's vacuum press often have the surface texture of oil paintings; Helen Frankenthaler’s tend to be two-dimensional, like Titus-Carmel’s: see Grand Intérieur I-III). Normally, after each color is run, the paper is put in a rack until the paper and ink are dry enough for the next color run.

Selected Bibliography: Henry Geldzahler, Tim Hilton, and Dominique Fourcade, Jules Olitski (NY: Salander-O'Reilly, 1990—these texts were part of a 5-volume set that accompanied exhibitions in London, Madrid, New York, and Beverly Hills CA), Carl Belz, Jules Olitski—Matter Embraced: Paintings 1950s and Now ( NY: Knoedler & Co., 2005), Andre Emmerich Gallery, Jules Olitski—Paintings 1988 (NY: Andre Emmerich Gallery, 1988), Michael Fried, Jules Olitski: Paintings 1963-1967 (Washington D.C., 1968), Clement Greenberg, Jules Olitski: Communing with the power (Washington: Buschlein-Mowatt Gallery, 1989), Norman L. Kleeblatt, Jules Olitski: The Late Paintings. A Celebration ( NY: Knoedler & Co., 2008), Rosalind E. Krauss, Jules Olitski: Recent Paintings (Cambridge: M.I.T., 1968); Neil Marshall, Jules Olitski: New Paintings (NY: Andre Emmerich Gallery, 1978); Kenworth Moffett, Jules Olitski (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1973); Kenworth Moffett, Olitski: New Sculpture (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1977; after the show closed at the MFA, it travelled to the Hirschhhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 1977); David W. Moos, Jules Olitski: Embracing Circles 1959-1964 (San Francisco: Hackett-Mill, 2010), Bruce W. Pepich, Jules Olitski (Art Gallery International, April 1990, 14-18), Judith Stein, Jules Olitski: An Inside View. A Survey of Prints 1954-2007 (Brattlebooro VT: Brattlebooro Museum and Art Center, 2008), Karen Wilkin and Stephen Long, The Prints of Jules Olitski: A Catalogue Raisonné 1954-1989 (NY: Associated American Artists, 1989).

|

|

|

|