|

|

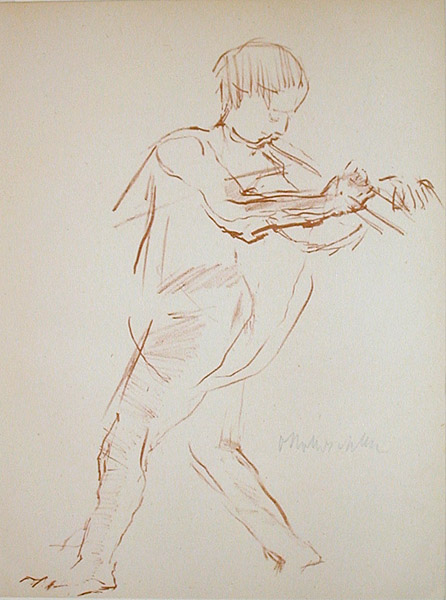

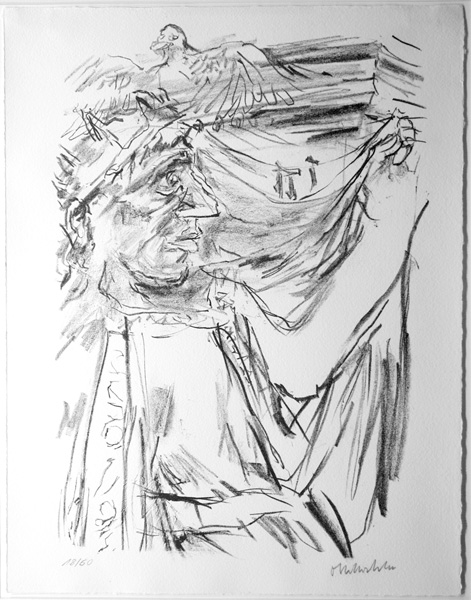

"Oskar Kokoschka was born at Pöchlarn on the Danube in 1886. His father was Czech and came from a well known family of Prague goldsmiths. He was perhaps rather work-shy: Kokoschka later said of him, 'From him I learned to endure poverty rather than work slavishly at distasteful work.' His mother came from the mountain region of Styria, and claimed to have second sight. As a boy, Kokoschka was not particularly attracted to art. He wanted to study chemistry but was recommended for a scholarship at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts by a teacher who had been impressed by his drawings. He entered the School in 1905, the year in which he started to paint in oils, and in 1907 he found work at the Wiener Werkstotte. Soon he began to expand his activities to literature. Asked to produce a children's book, he wrote his own text, Die Traumenden Knaben (The Dreaming Youths), which was scarcely suitable for the young, but made a good basis for his distinctive illustrations. He also wrote two plays, Sphinx und Strohamann (The Sphinx and the Scarecrow), and Murder, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murderer, Hope of Women): these are now considered to mark the beginnings of Expressionist theatre in Germany.

"In 1908 Kokoschka's work was shown in the Kunstschau exhibition in Vienna, which featured the avant-garde group around Klimt. His contributions were a centre of controversy because of their Expressionist violence, and he was dismissed from the School of Arts and Crafts as a result. In 1909 his work was shown at the second Kunstschau, and his two plays were performed in the little open-air theatre attached to the exhibition buildings. There was a tremendous scandal because of their violence, and their unconventional and apparently irrational structure, and even the Werkstotte would no longer employ him. At one time he managed to keep alive by betting on his own capacity to drink visitors to Vienna under the table. His chief protector was the pioneer Modernist architect Adolf Loos, who secured portrait commissions for him. One portrait was of the satirical writer Karl Kraus, editor of Die Facket (The Torch). Kraus said of this: 'It is quite possible that those who know me will not recognize me. But it is certain that those who do not know me will recognize me.'

"In 1910 Kokoschka's luck changed. He went to Berlin and was taken up by Herwarth Walden, the energetic owner-editor of Der Sturm, who commissioned him to do title-page drawings for the magazine and used one for almost every issue. He was also given a contract by the powerful dealer Paul Cassirer. In 1911 he returned to Vienna and was appointed as assistant teacher at the very school which had dismissed him. He had a show at the Hagenbund in Vienna, of which the opening reception was attended by Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne, who exclaimed indignantly: 'This fellow's bones ought to be broken in his body!' Most important of all, in 1911 he began a passionate affair with Alma Mahler, the widow of the great composer, an elegant society beauty considerably older than himself. The year 1912 was better still—he was able to give up teaching and showed at the Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne, which united the whole German-speaking avant garde, and with the Blaue Reiter in Munich.

"By 1913 his relationship with Alma Mahler was beginning to show signs of strain. They travelled to Italy together, and on one occasion visited the Naples aquarium. Kokoschka watched an insect sting and paralyse a fish, before devouring it, and at once associated the scene with the woman by his side.

"He was still a controversial figure: when he began teaching art at a smart Viennese girls' school whose headmistress was known for her progressive views, some of the parents objected so strongly that the Austrian government actually banned him from teaching. War, when it broke out, seemed a release from an impossible relationship and an impossible situation. Adolf Loos used his influence to have him appointed Lieutenant in an exclusive regiment of dragoons with a particularly glamorous uniform. As soon as the appointment was gazetted Loos had a postcard made of Kokoschka in his finery which was sold in shops alongside those showing leading actresses.

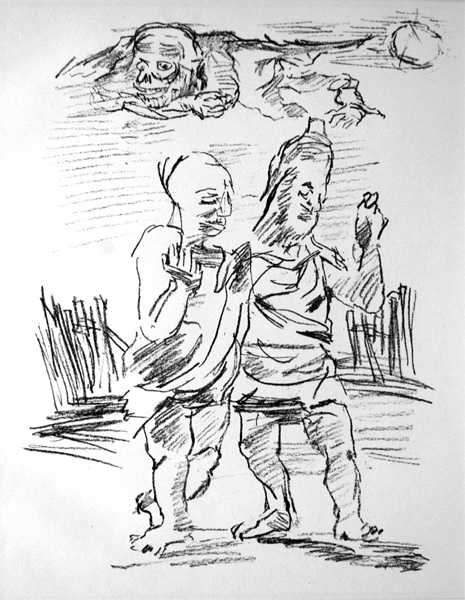

"At the beginning of 1915 Kokoschka was seriously wounded—and briefly taken prisoner—in Galicia: he suffered a head injury and a bayonet wound to the lung. He spent a period of convalescence in Vienna, but was then sent to the Isonzo Front, where his health soon broke down completely. He went to Stockholm to consult a brain specialist and then to Dresden to try and recover his health. His anguish was as much mental as physical, and was perhaps connected with his residual feelings for Alma Mahler. To exorcize his obsession he commissioned a life-sized doll, complete and life-like in all details, which he treated like a living companion—it has even been said that he escorted it to the opera.

"After the end of the war the political situation in Dresden was very unstable, just as it was everywhere else in Germany, and Kokoschka formed part of a small, left-wing bohemian group. In the newly liberal climate of 1919 he was officially appointed Professor at the Dresden Academy, and this post brought with it a beautiful house and studio. Outside Dresden, his reputation continued to rise. The composer Paul Hindemith set Murderer, Hope of Women to music, and it received numerous performances, among them one at the Dresden State Opera. In 1922 Kokoschka was invited to exhibit at the Venice Biennale. His health had now improved and he was becoming restless. He resigned his post at the Dresden Academy in 1924, simply giving a note to the porter and leaving the city before his intentions had been discovered. A period of travel followed, financed by the proceeds of his now lucrative Cassirer contract. Using Munich as his main base he went all over Europe, and also to North Africa, Egypt, Turkey and Palestine. The year 1931 brought great success for him, despite the darkening political horizon: he had a show at the Kunsthalle in Mannheim which Cassirer's successors brought to the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris, where it did well with the Parisian public. However, from this triumph there also came a conflict. Kokoschka demanded more independence from his dealers; they, in turn, were anxious to establish his work as a staple commodity in the art market. Kokoschka broke with them, and there was an acrimonious exchange of letters in the Frankfurter Zeitung.

"In 1932 Kokoschka once again showed at the Venice Biennale, but now his reception was stormy. Mussolini made it plain that he disliked Kokoschka's art, and the pro-Nazi press in Germany seized the opportunity to attack him. By 1933 his finances were severely strained, and he left Paris for the provinces and then went to Vienna to be with his mother. He felt ill at ease in a city ruled by the fascist administration of Chancellor Dollfuss, and after his mother's death later that year he went to Prague and took Czech citizenship. The Austrian government tried to lure him back by offering him the Directorship of the School of Arts and Crafts, and in 1937 he was the subject of a major retrospective at the Osterreiches Museum fur Kunst und Industrie This perhaps meant less to him than the fact that his work was also on show that year in the Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich—at the same time more than four hundred of his works were removed from German museums. In Prague he had met Olda Pavlovska, who was later to become his wife, and he was busy expressing support for the Republic cause in Spain.

"The Munich Agreement of 1938 indicated that Prague was no longer a safe refuge. In September Kokoschka left for England. This was the logical choice, but it was also the only place in Europe where his art was very little known. The Kokoschkas were desperately poor. In 1939 they moved to Polperro in Cornwall where Oskar made watercolours of the local scenery and Olda ran a pastry shop to help their finances. The next year, however, they returned to London, as Kokoschka was convinced that their neighbours were suspicious of them. London bored and depressed him:

What am I to do in this hole [their London flat] ? I must invent new subjects for my paintings. I am quite starved for something to see. When the spring comes I feel how it stirs in me as in a migrant bird, and I become quite nervous: I must leave town and paint something real—a grasshopper or something. When I come back to town the landscapes turn into political pictures. My heart aches, but I cannot help it. I cannot just paint landscapes without taking any notice of what happens.

"His fortunes began to look up as soon as the war was over. In 1945 he received a symbolic tribute in war-battered Vienna: an exhibition shared with Klimt and Schiele, both long dead. In 1947 there was a large Kokoschka retrospective at the Kunsthalle in Berne, and in 1952 a room was devoted to his work at the 26th Venice Biennale, Kokoschka had become a British citizen in 1947, but was not eager to remain in a country which he felt had slighted him. In 1953 he began to run his School of Seeing at the Internationale Sommerakademie fur Bildende Kunst in Salzburg, thus re-establishing his ties with the Austrian milieu in which he began his career, and in the same year he settled permanently at Villeneuve on Lake Geneva. He was now once again an extremely celebrated artist, but he had drifted away from the post-war art world, and, though much respected, was a marginal figure by the time of his death in 1980." (Text from Edward Lucie-Smith, Lives of the Great 20th-Century Artists [London: Thames & Hudson, 1999], 81-83)

Since his death, there has been a revival of interest, coupled with a series of retropectives of his work (particularly the 1986 exhibition and accompanying book at the Goggenheim Museum). Dr. Heinz Spielmann has suggested in his introduction to a 1981 retrospective shown in both London and New York by his dealers, Marlborough Fine Arts and Marlborough Gallery, "Kokoschka's genius is displayed in his paintings and drawings no less than in his poems, dramas, and essays: he is invariably direct, often violent, always vivid and unconstrained. The basis of Kokoschka's ethical doctrine was that everyone must use his freedom even though it should lead to conflict or death. Consequently his art, even in life, is always dramatic and imbued with passionate sympathy." In an age when all of our options so often seem like choices between lesser evils, Kokoschka affirms the need to choose and to act and to accept the consequences however imperfect and to accept as well the responsibility for those choices.

Kokoschka's works are parts of the permanent collections of almost every major museum in the world.

Selected Bibliography: Richard S. Field, Oskar Kokoschka (Storrs: William Benton Museum of Art, The University of Connecticut, 1977; E. H. Gombrich, Kokoschka in His Time (London: Tate Gallery, 1986); E. H. Gombrich, Bethusy-Huc, Fritz Novotny, Hans Bolliger, Jan Tomes, Bernhard Baer, Homage to Kokoschka: Prints and Drawings lent by Reinhold, Count Bethusy-Huc (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1976); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Oskar Kokoschka 1886-1980 (NY: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1986); J.P. Hodin, Kokoschka: The Artist and His Time (Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1966); Oskar Kokoschka, My Life trans, David Britt (NY: Macmillan, 1974); Oskar Kokoschka, Oskar Kokoschka : Letters, 1905–1976 selected by Olda Kokoschka and Alfred Marnau, foreword by E. H. Gombrich (London: Thames & Hudson, 1992); Ernest Rathenau, ed., Oskar Kokoschka Drawings, 1906-1965 (Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1970); Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Orbis Pictus. The Prints of Oskar Kokoschka 1906-1976 (Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1987); Serge Sabarsky, Oskar Kokoschka: Die Fruhen Jahre. Zeichnungen und Aquarelle (catalogue for a traveling retrospective shown at the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (9 December 1982 - 30 January 1983); Museum Villa Stuck, Munchen (7 April - 24 May 1983); Neue Galerie der Stadt Linz, Wolfgang Gurlitz Museum (31 May - 17 July 1983); Salzburger Museum Carolino Augusteum (22 July - 4 September 1983; published Vienna, 1982); Serge Sabarsky, Oskar Kokoschka Drawings and Watercolors The Early Years: 1906 to 1924 with essays by Serge Sabarsky, Oskar Kokoschka, and Achille Bonito Oliva (NY: Rizzoli, 1983); Fritz Schmalenbach, Oskar Kokoschka (Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1967); Klaus Albrecht Schroder and Johann Winkler, ed. Oskar Kokoschka (Munich: Prestel, 1991); Staatliches Museum Schloss Burgk, Oskar Kokoschka: Buchillustrationen 1908-1970 (Pirckheimer-Kabinett: Staatliches Museum Schloss Burgk, 1981); Tate Gallery, Oskar Kokoschka 1886-1980 (London: Tate Gallery 1986); Peter Vergo, Art in Vienna, 1898–1918. Klimt, Kokoschka, Schiele and their Contemporaries (London: Phaidon, 1975); Frank Whitford, Oskar Kokoschka A Life (London: Weidenfeld And Nicolson, 1986); H. M. Wingler and O. Welz, Oskar Kokoschka. Das druckgraphische Werk. 2 Vols. (Salzburg: 1975-80; Catalogue Raisonne of the Complete Prints with 567 works illustrated); H. M. Wingler, Oskar Kokoschka: The Work of the Painter (Verlag Galerie Welz, 1958); Johann Winkler & Katharina Schulz, Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980): The Late Work, 1953-1980 (London: Marlborough Fine Art, 1990).

|

|

|

|