|

|

Gérard Titus-Carmel is an artist of the same generation as my wife and I. Born in 1942, he, like the others of our time, grew up in an international world, a world where national boundaries exist as memories of a world we can no longer afford, a world of national interests, rivalries, wars. Born during the second world war, we know it only through the nightmares of our parents, the memories of our elders. We are the children of the bomb, survivors of grade school civil-defense exercises in case of nuclear attack, the adolescents of the nervous and electric rhythms of hard-bop, voyagers with musicians like Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy (with whom Titus, a drummer, played, for one set, once) and John Coltrane, explorers of the musical unknown. We have listened to the same music, read some of the same books, visited many of the same places, looked at much of the same art. Living in the same world, and trying to come to terms with the things that shaped it, we came of age during the Cuban Missile crisis with its threat of a holocaust greater than any that haunts the dreams of our parents' generation. We have lived almost our entire lives in a world held in uneasy peace only by the threat of "Mutual Assured Destruction." Yet we have also walked in the ruins of Monte Alban and stood in the ball court of the Olmecs; we have listened to ancient mariners as the surf laps the shores bordering the oceans of our dreams. For our generation, the problem has been one not so much of finding reality, but of finding a reality that will permit us to live not just within our world but within ourselves as well. For that effort, we need more than the "super-realism" or the theatrical "neo-expressionism" of the '80s, more than an art that commercially derides "the system" for being too commercial; we need an art that can take us beyond the surfaces, that remembers its past and our past, that can teach us what to remember and how to forget what we do not need to remember to go on with life.

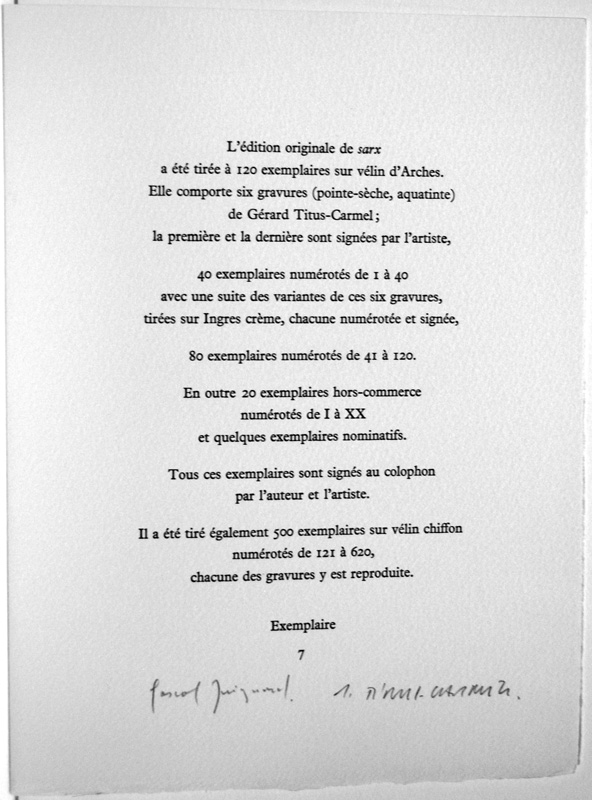

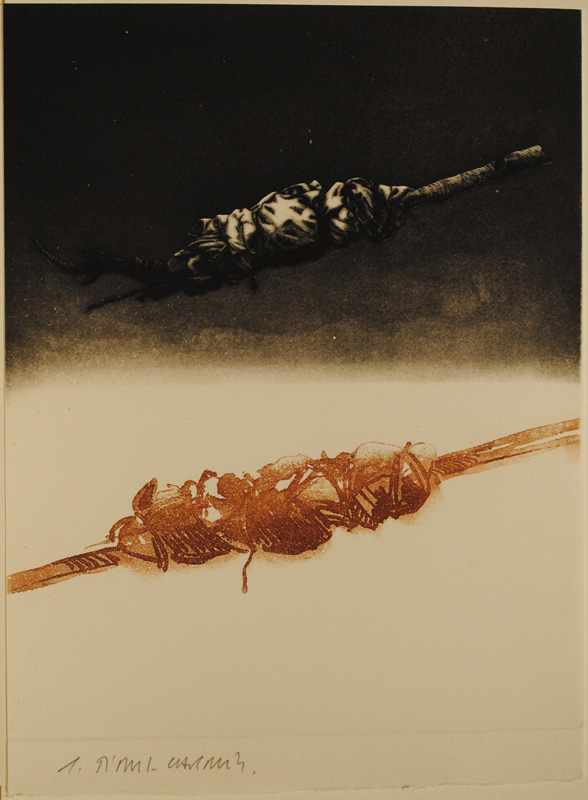

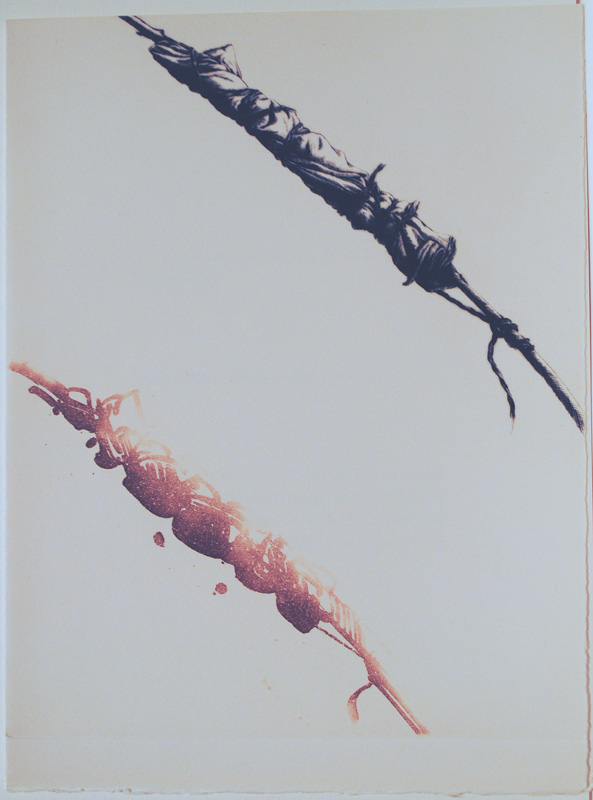

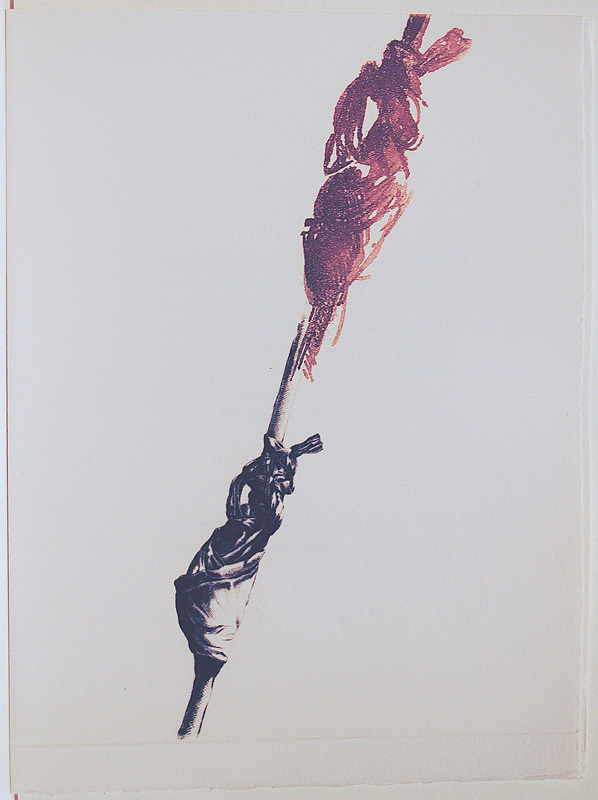

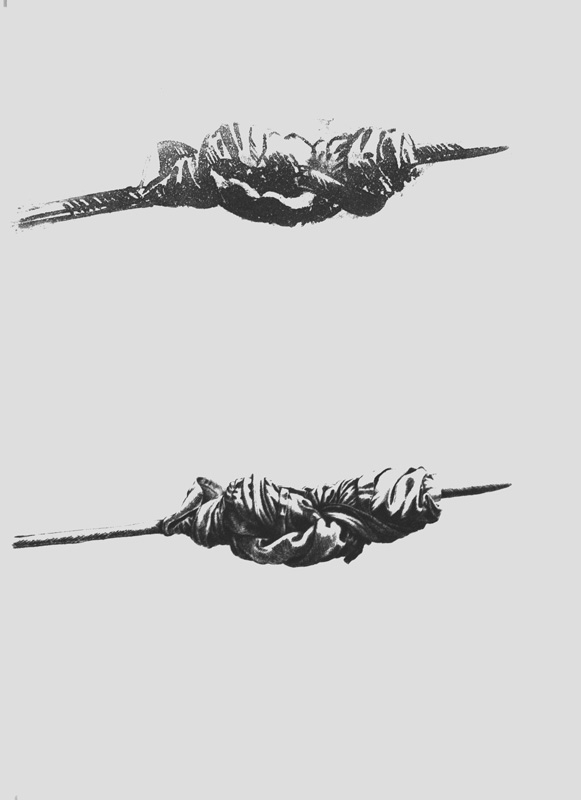

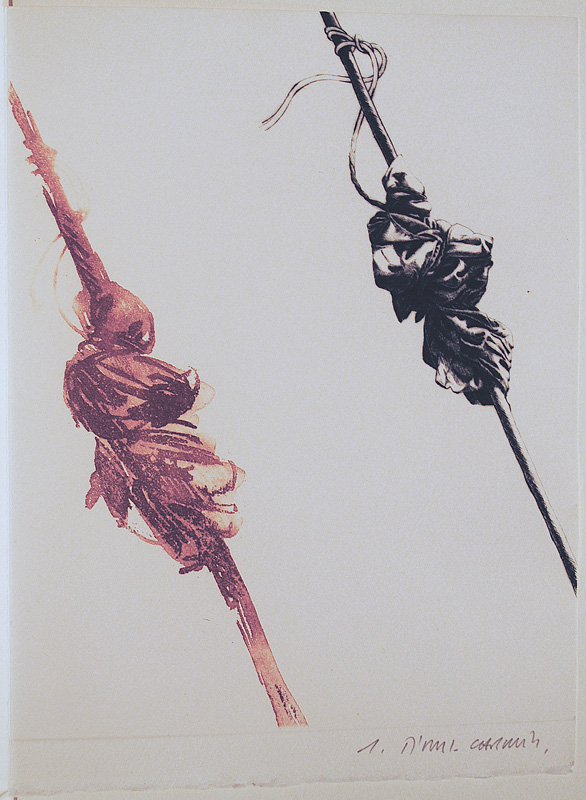

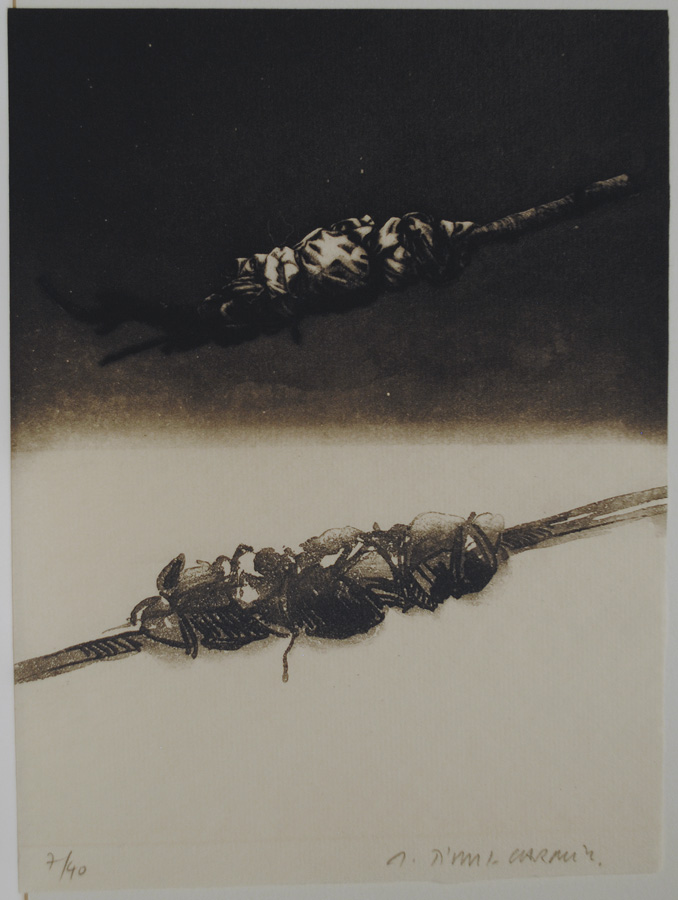

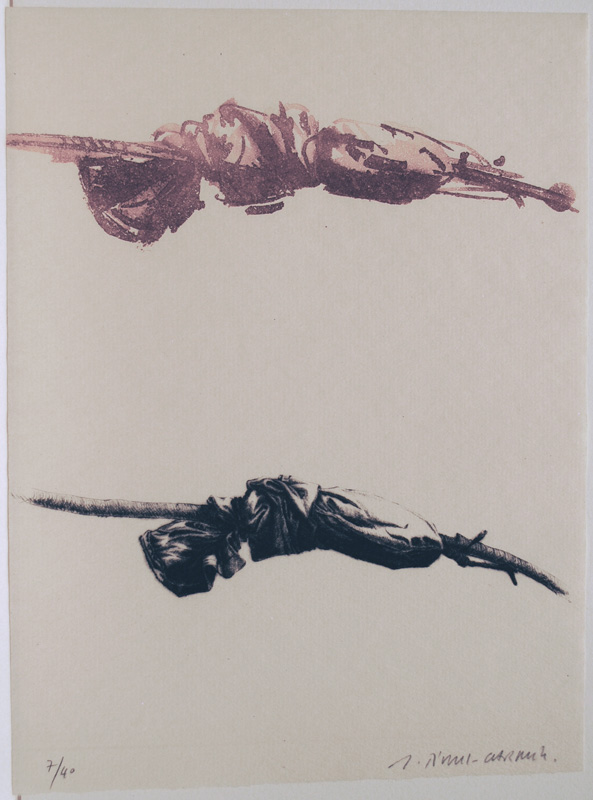

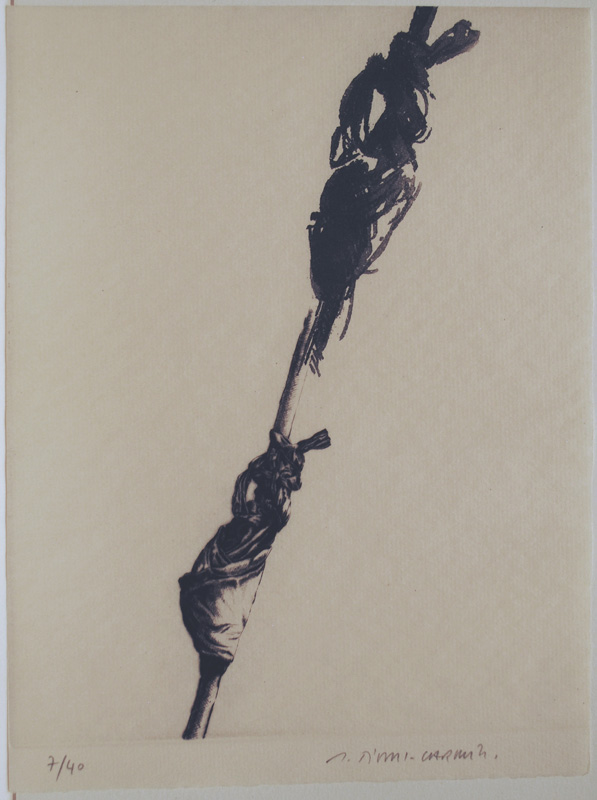

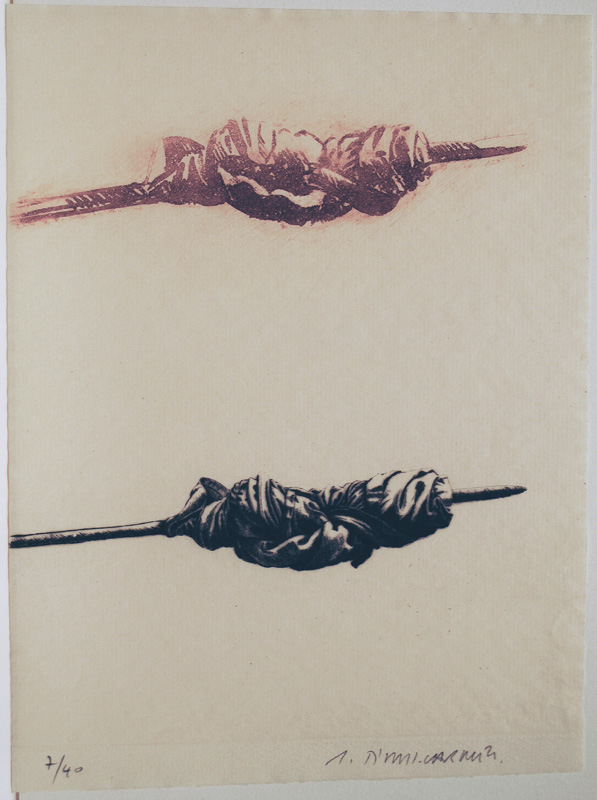

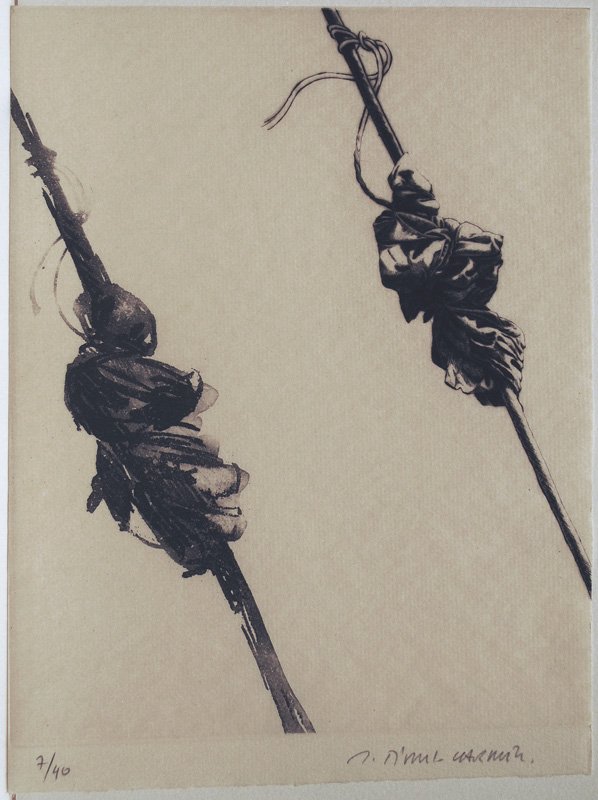

Titus-Carmel has collaborated with poets on a number of livres-d'artiste and has also written more than 30 books of poetry, some of which he has also illustrated. From the fact that the Museum of Modern Art included Sarx and the 6 drypoint and aquatint works it contained into a major exhibition (and book of the same title by Riva Castleman, Director of Prints and Illustrated Books at MoMA), Printed Art: A View of Two Decades [NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1980), I think that we may safely assume that this is a work that deserves a careful consideration. Happily for those of us whose French has gone south for the winter, Pascal Quignard's verse text has also been translated by Keith Waldrop (Providence: Burning Deck, 1997). "Sarx," of course, is Greek for "flesh," hence the word sarcasm, which we learn (on p. 10), originally signified "The insult delivered to an opponent's dead body. Irony born of bitterness. Speech inverted." Each of the 6 prints in the work (like all livres d'artiste, the plates are unbound, contained in a folder within a case), contains two views of what may have been the same object, one perhaps out-of-focus, perhaps decomposing, perhaps not yet composed; the other very sharp, but also combining patches of pure white with very dark tones that demand study or they refuse interpretation as objects. Viewing (confronting?) these works in the flesh (so to speak) is a very different experience than looking at our photographs of them. The works themselves run a chromatic range from pure white to deepest black, from utmost clarity to fuzzy haziness (just like life itself?) that defies easy comprehension while it demands our full attention. And yet the Quignard text calls meaning into question sometimes ("Meaning is of no account Counts for nothing. Death' [p. 11]), while at other times it suggests that it is all we have ("Language is this bid of the mourner, bound to the dead other as other, singular enemy. Furies of terror levy terrified flesh in order to suspend terror, spread out, terrified, in order to save from violence, do violence, violate" [p. 30]). Art and poetry may not be the answer, but on the other hand, they may tease us into believing that there are answers that we might someday, somehow struggle to discover if not in our works, then, perhaps, finally, in our flesh.

In his essay in presentation of the Suite Chancay (Repères, 1985) Jacques Henric suggests that Titus' wrapped sticks reminded him of the expression, "You might as well bandage a wooden leg," and concludes that such may well be the job of the artist today, "a sort of Mister First Aid in white, kit in hand, running from one end of the planet to the other (at times without leaving his studio) to repair all the damage, but the damage he has the feeling he himself caused." This seems to me to be more often than not the case; the remainder of the time, it may be the case, or perhaps not. Far more than bandaging the broken objects of our lives, Titus-Carmel’s art bandages our broken lives themselves. His images have a dramatic quality that denies their factual existence as two-dimensional objects. His work is for us a necessary restorative. Like Shakespeare's King Lear in search of remedy, we need artists like Titus-Carmel to "sweeten" our imagination so that we may continue to discern and to live out the miracle of our lives.

Titus-Carmel is one of the most written-about contemporary French artists, having been the subject of studies by Jacques Derrida, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Gilbert Lascault, Werner Spies, Jean Pierre Faye, Denis Roche, Jean Louis Schefer, and many others. He is also one of the most widely shown artists of his generation (b. 1942), having received over 400 group ahows and over150 one–person shows at museums and galleries including The Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris (1971), the 1972 and 1984 Venice Biennales, the Royal College of Art in London (1972), the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1973), the Palais des Beaux Arts, Brussels (1975), the Centre Georges Pompidou / Musée National d'Art Moderne (1978), the Museums of Dusseldorf (1979), Bielefeld (1980), Kassel (1980), Nuremberg (1981), Oslo (1981), Lubceck (1981), Les Sables d'Olonne (1981), Luxemburg, Calais, (1984), Nice, Carcassonne, and Lille (1985), Quebec (1986), Budapest, and Châteauroux (1987), Caen (1989), Montaubon and Avignon (1990), and Tokyo (1991). In addition, the French Cultural Ministry also organized touring exhibits at the Instituts Français of Stuttgart, Hamburg, Munich, and Bonn (1985), Damascus, Aleppo, Alexandria, Cairo (1990-1991), and Palermo, Naples, and Rome (1991). His works are in the permanent collections of over 100 public institutions including the Guggenheim Museum (New York), the Museum of Modern Art (N.Y. and Paris), the Chicago Art Institute, the Bibliotheque National and the Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris), the Victoria and Albert Museum (London), and many others. He has also participated as the official delegate for France in numerous international exhibitions, such as the Biennial of Paris (Paris, 1969), Expo ’70 (Osaka, 1970), the Biennial of Alexandria (Alexandria, 1971), “Amsterdam-Paris-Düsseldorf ” (Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1972), Dokumenta VI (Kassel, 1977), “European Dialogue” (the Sidney Biennial, 1979), “Statements/Leading Contemporary Artists from France”(New York, Dallas, San Francisco, Seattle, 1982), Biennale Internazionale Arte (Venice, 1972 and 1984), “Gerard Titus-Carmel: Forging the Real” (Spaightwood Galleries, 1988), Art in France: a Century of inventions (Moskva , Leningrad, 1989), “Contemporary Art in France” (French Pavillion, Universal exposition, Sevilla, 1992), Fonds regional d’art contemporain de Picardie (1993), the Instituts Français of Casablanca, Rabat, Tangier, and Tetuan (1995), Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, Issoudun (1997), Soissons (1998), Titus-Carmel: Une decennie (a large-format hardcover published by Editions Palantines, 2000 to accompany a touring show that went to 5 French museums documented many of the series of the preceding 10 years), another large-format work, Gérard Titus-Carmel: La parte du livre (Reims: Bernard Dumerchez éditeur, 1995) documented Titus’ involvement with books (whether as writer, illustrator, or subject), François-Marie Deyrolle, ed. La Geste & la Mémoire: Regardes sur la peinture de Gérard Titus-Carmel (Ain: L’Act Mem, 2007) contained 28 brief essays collected from prefaces to various exhibition catalogs between 1973 and 2006) by a wide range of poets, novelists, and art critics among others. In 2007, Michael Bishop’s The Endless Theory of Days: The Art and Poetry of Gérard Titus-Carmel (NY: Rodopi, 2007), the first full-length study of Titus as artist and poet in English. Last, but hardly least, in 1987, the University of Chicago Press published Jacques Derrida, The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian MacLeod, chapter 3 of which contains an English translation of Cartouches, the essay that Derrida wrote in 1978 to introduce the installation of Titus’ exhibition of The Pocket Size Tlingit Coffin, a collection of 127 mixed-media drawings on an imaginary object that Titus invented, manufactured, and drew over the course of a year and which the Musée national d’art moderne at the Centre Pompidou purchased in its entirety.

|

|

|