|

|

Gérard Titus-Carmel is an artist of the same generation as my wife and I. Born in 1942, he, like the others of our time, grew up in an international world, a world where national boundaries exist as memories of a world we can no longer afford, a world of national interests, rivalries, wars. Born during the second world war, we know it only through the nightmares of our parents, the memories of our elders. We are the children of the bomb, survivors of grade school civil-defense exercises in case of nuclear attack, the adolescents of the nervous and electric rhythms of hard-bop, voyagers with musicians like Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy (with whom Titus, a drummer, played, for one set, once) and John Coltrane, explorers of the musical unknown. We have listened to the same music, read the same books, visited many of the same places, looked at much of the same art. Living in the same world, and trying to come to terms with the things that shaped it, we came of age during the Cuban Missile crisis with its threat of a holocaust greater than any that haunts the dreams of our parents' generation. We have lived almost our entire lives in a world held in uneasy peace only by the threat of "Mutual Assured Destruction." Yet we have also walked in the ruins of Monte Alban and stood in the ball court of the Olmecs; we have listened to ancient mariners as the surf laps the shores bordering the oceans of our dreams. For our generation, the problem has been one not so much of finding reality, but of finding a reality that will permit us to live not just within our world but within ourselves as well. For that effort, we need more than the "superrealism" or the theatrical "neo-expressionism" of the '80s, more than an art that commercially derides "the system" for being too commercial; we need an art that can take us beyond the surfaces, that remembers its past and our past, that can teach us what to remember and how to forget what we do not need to remember to go on with life.

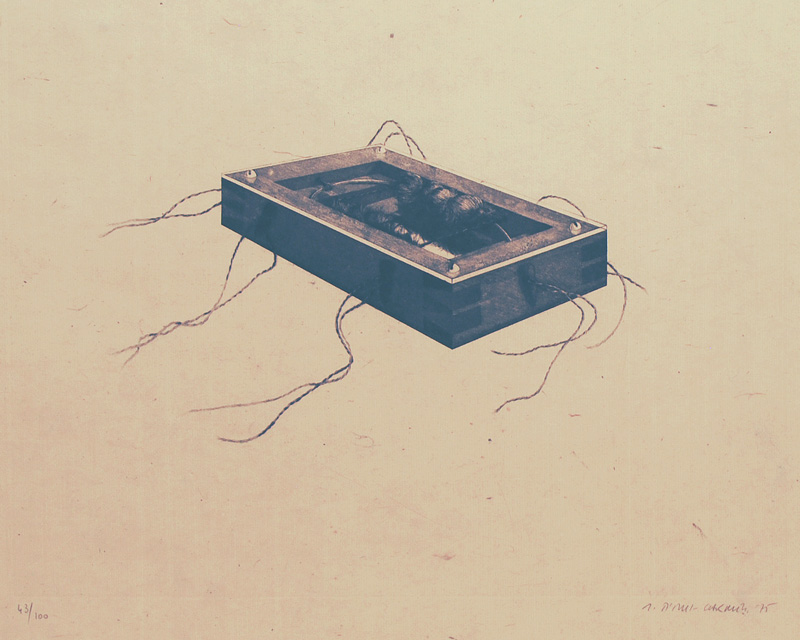

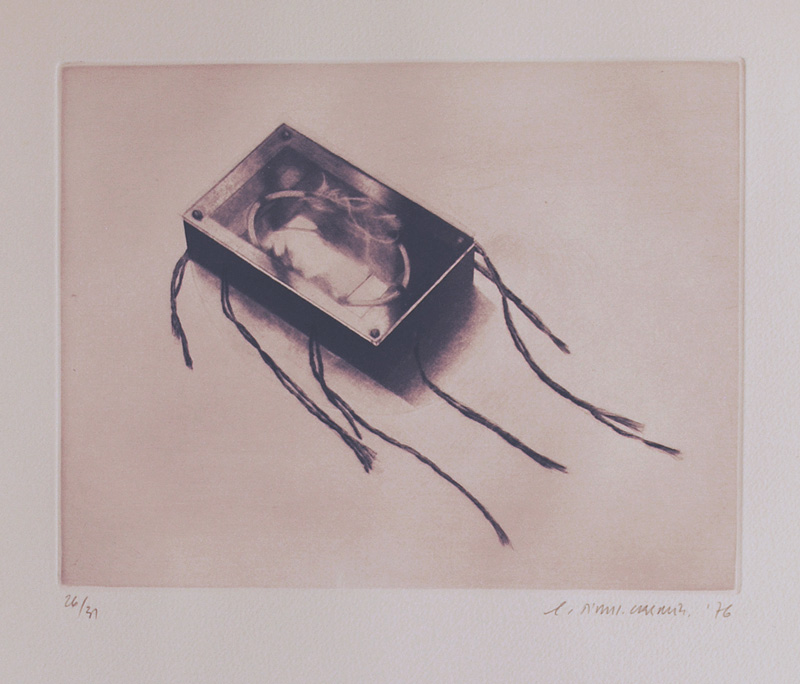

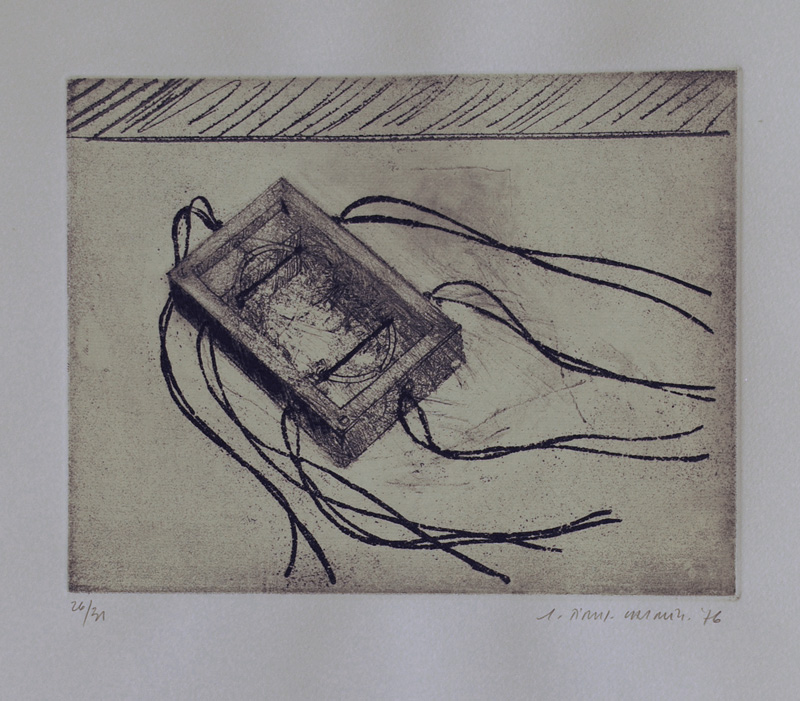

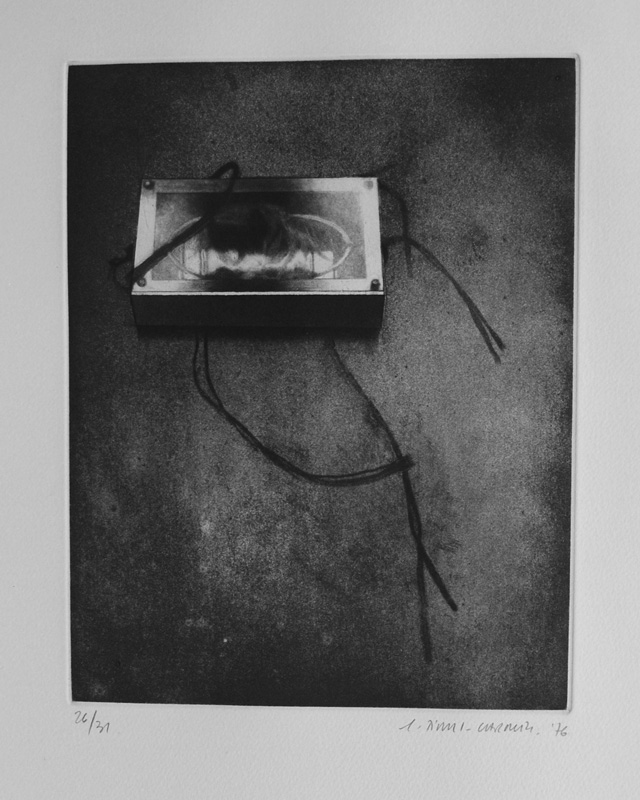

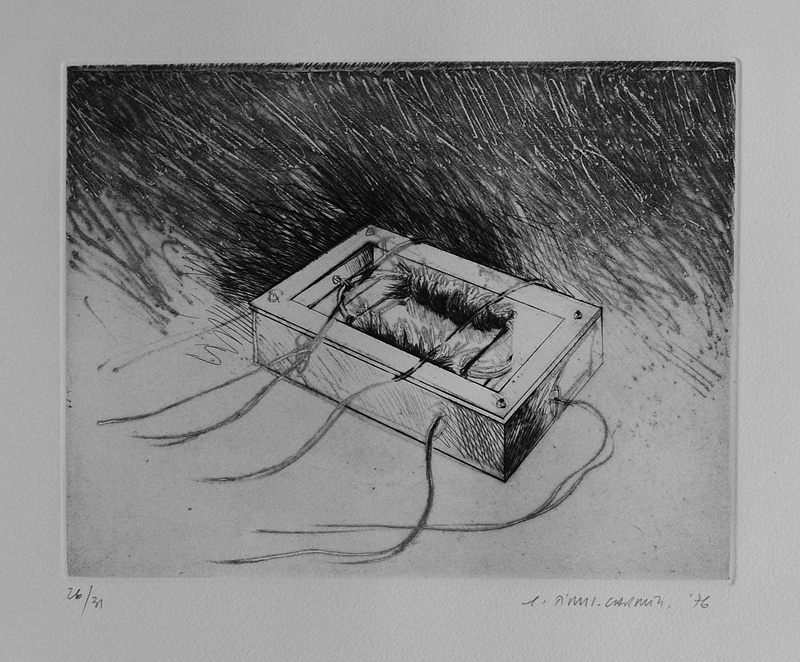

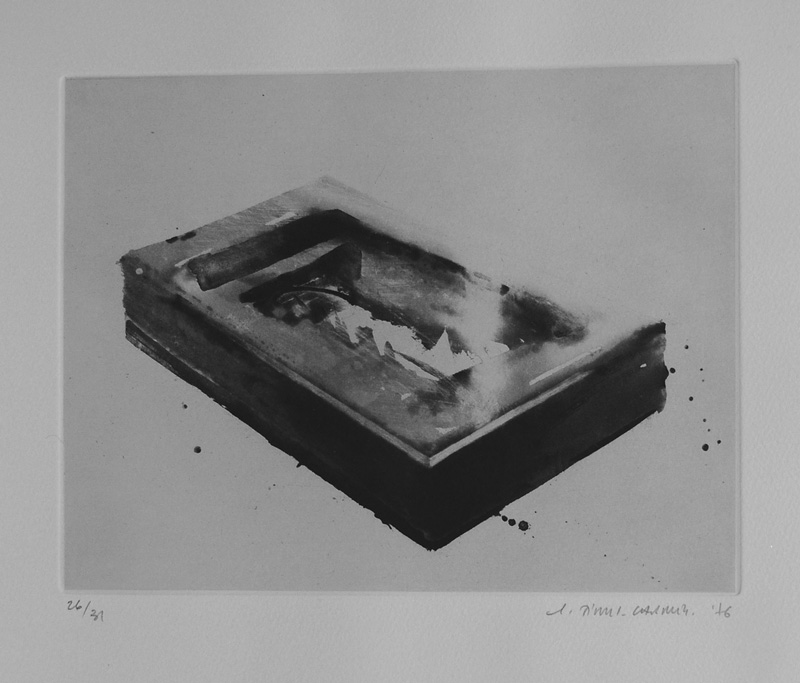

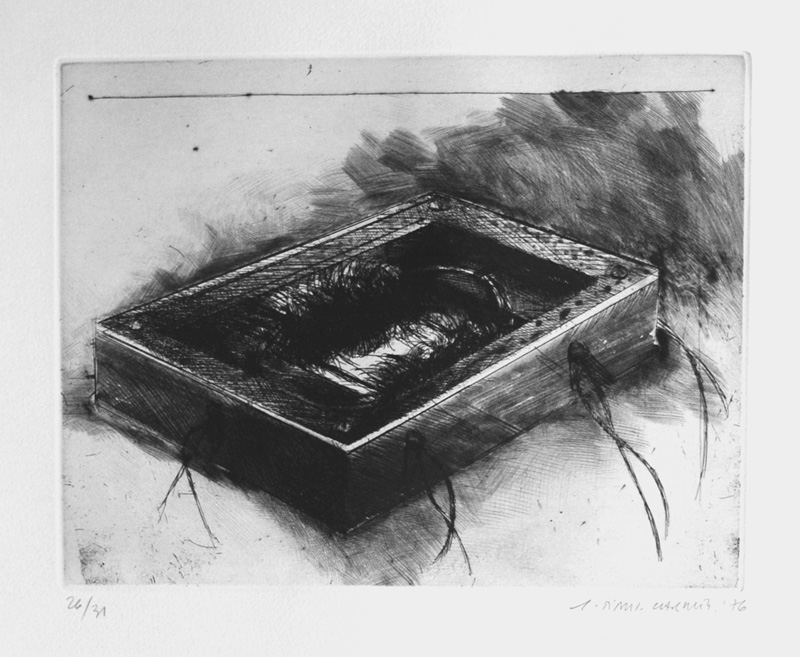

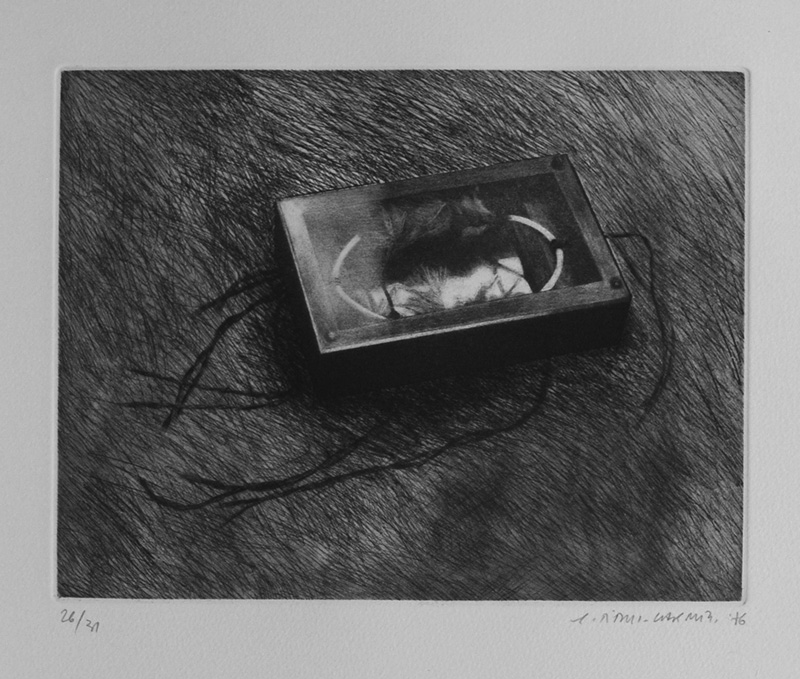

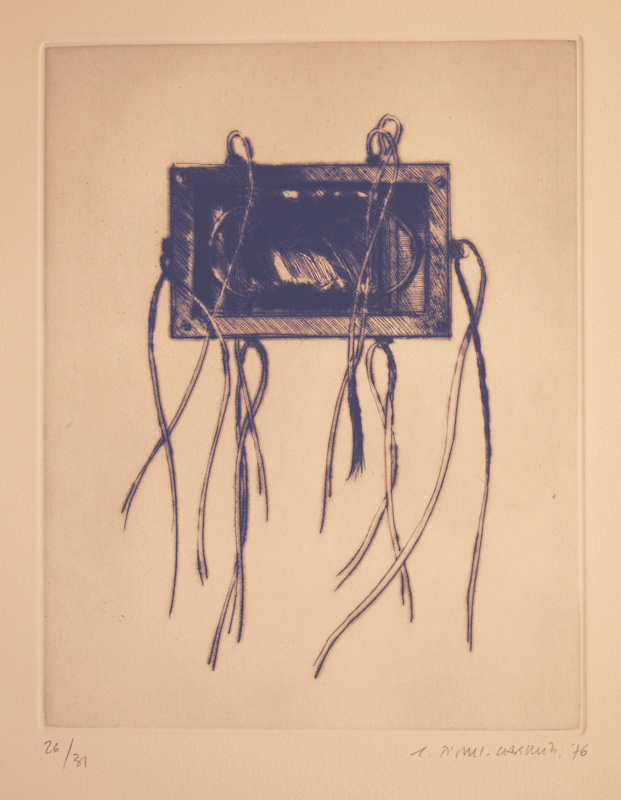

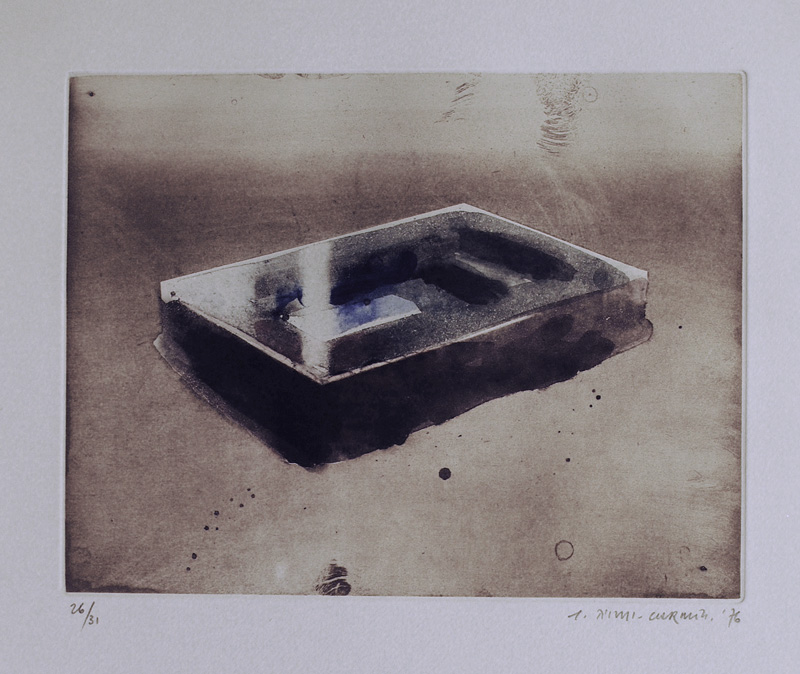

In a 1976 booklet, Titus-Carmel describes the origins of one of his most successful series, The Pocket Size Tlingit Coffin, or: Of lassitude considered as a surgical instrument: "Assembled under the title of The Pocket Size Tlingit Coffin are a large number of drawings (127, to be exact), all outlining [from the very first words, insidiously, matters are clear: outlining in the sense of having the force of the stroke. Tracing, drawing, a line (an arrow) on the model] the same model: a mahogany box of modest dimensions (10 x 6.2 x 2.4 cms). . . . On page 20 of Jean Genet's Pompes Funèbres, we find: 'In my pocket, the box of matches, the minute coffin, imposed its presence more and more and obsessed me.' Further on: 'It was not necessary that the coffin, of reduced dimensions, be real. On this small object the coffin for solemn funerals had imposed its power.' Rolling of the drums." The Pompidou center bought the entire series, made a movie based upon the creation of the series, asked Jacques Derrida to write an introduction to the catalogue of the exhibition (later to become chapter 3 in Derrida's book, Truth in Painting).

Missing models of unreal objects, of sticks born in the marriage of memory and chalk, of a Tlingit coffin made of reed ovals wrapped on two sides with gray synthetic fur: what does their absent presence say to us? Models which exist only long enough for the artist to draw them, to trace their outlines on a sheet of paper, to force us, perhaps furtively, to look on their likenesses, their reproductions in pen, pencil, chalk, drypoint, etching, aquatint—why do we find them so fascinating, so obsessing? Titus-Carmel wondered about the same thing as he worked on the series: "We can also note the reactions of almost everyone confronted with the box (while, newly made and shining new—but somehow inexplicably weathered and worn—it was abandoned on some strand of the apartment): the visitor picks up the wreck with curiosity, manipulates it a moment, uncertain, and then, suddenly disturbed, almost embarrassed, quickly puts it back in its place in the shade. Nothing will be said about the box discovered and replaced so quickly, about that very abruptness, or the nature of the silence that follows."

Somehow, the series reminded me of one of William Butler Yeats' last poems, The Circus Animals' Desertion, whose final stanza reads as follows:

Those masterful images because complete

Grew in pure mind, but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder's gone,

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

These images of an unknown but at least semi-disturbing object (old bones, old flesh, old scraps?) are unsettling because despite their alienness, we cannot help recognize the virtuoso technique (or techniques) required to bring them into being, the large sheets of paper on which they are printed which dwarfs each image, the very small size of the edition, their possible place in relation to a very long series of drawings, now ensconced in a major museum: all of this data, all of this sensory invitation, all of this puzzlement at the nature of the image, the constantly varied viewing experience as we move from one technique to another, one work to another, all focusing our attention on this mysterious object, somehow these images force us to consider the nature of perception itself as we wander through our varied world stuffed with luxury items and junk, trash and treasure, and wonder how we are to respond to them, to evaluate them, to accept or reject them. It may also make us wonder whether these works initiate us into a journey to the heart of darkness or the clarity of eternity.

Titus-Carmel is one of the most written-about contemporary French artists, having been the subject of studies by Jacques Derrida, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Gilbert Lascault, Werner Spies, Jean Pierre Faye, Denis Roche, Jean Louis Schefer, and many others. He is also one of the most widely shown artists of his generation (b. 1942), having received over 150 one–person shows at museums and galleries including The Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris (1971), the 1972 and 1984 Venice Biennales, the Royal College of Art in London (1972), the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1973), the Palais des Beaux Arts, Brussels (1975), the Centre Georges Pompidou / Musée National d'Art Moderne (1978), the Museums of Dusseldorf (1979), Bielefeld (1980), Kassel (1980), Nuremberg (1981), Oslo (1981), Lubceck (1981), Les Sables d'Olonne (1981), Luxemburg, Calais, (1984), Nice, Carcassonne, and Lille (1985), Quebec (1986), Budapest, and Châteauroux (1987), Caen (1989), Montaubon and Avignon (1990), and Tokyo (1991). In addition, the French Cultural Ministry also organized touring exhibits at the Instituts Français of Stuttgart, Hamburg, Munich, and Bonn (1985), Damascus, Aleppo, Alexandria, Cairo (1990-1991), and Palermo, Naples, and Rome (1991). His works are in the permanent collections of over 100 public institutions including the Guggenheim Museum (New York), the Museum of Modern Art (N.Y. and Paris), the Chicago Art Institute, the Bibliotheque National and the Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris), the Victoria and Albert Museum (London), and many others. Museums have twice organized complete retrospectives of his prints (in 1979 and 1991), each time publishing catalogues raisonnés. He has been the subject of seven films, including one produced by the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou and RTL Télévision, Luxembourg, and innumerable books, essays, exhibition catalogues, and reviews. Among his awards are first prize at the 2nd International Exposition of Original Drawings at Rijeka (1970), the Grand Prize at the 6th International Print Biennial at Krakow (1976), and the Jurors’ Special Award of Honor at the 1977 World Print Competition in San Francisco. Titus-Carmel is deservedly one of the best-regarded painters, draftsmen, and printmakers in the world today.

|

|

|

|