|

|

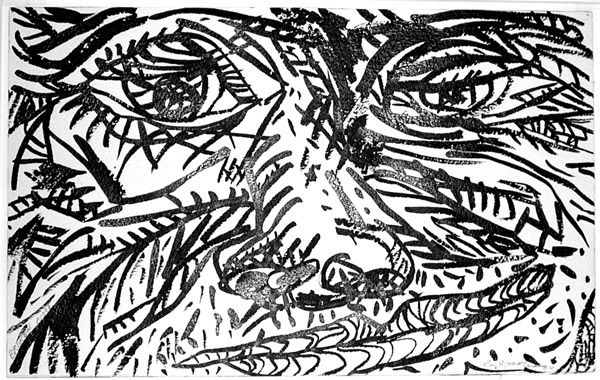

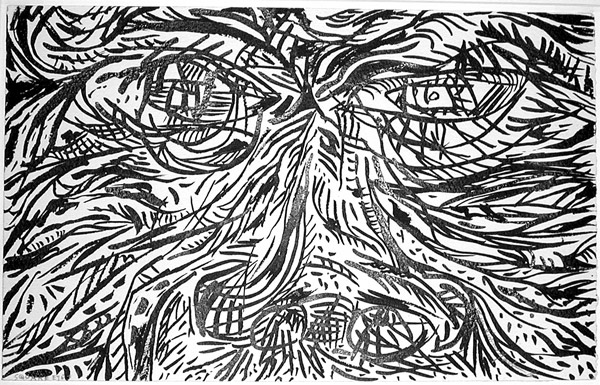

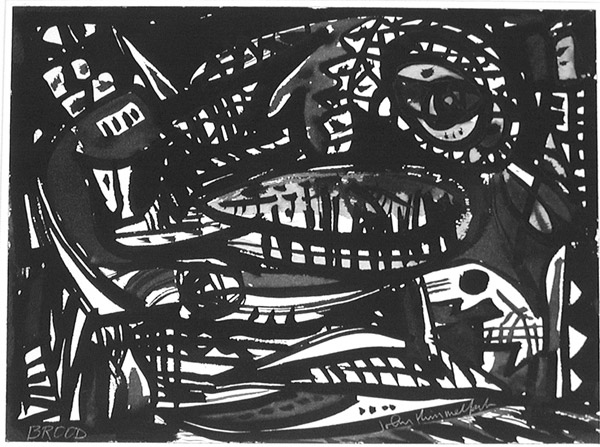

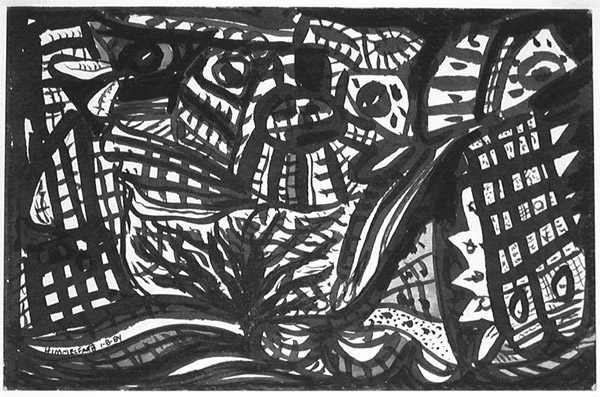

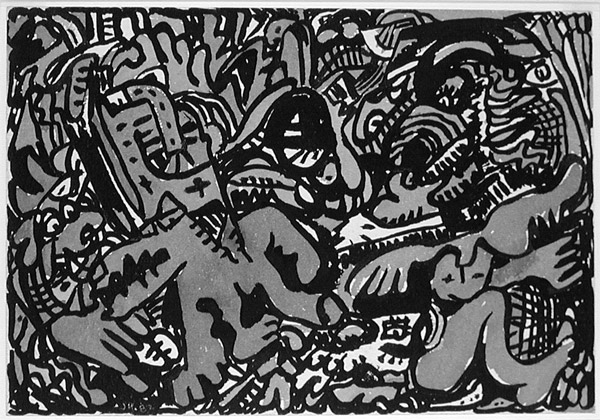

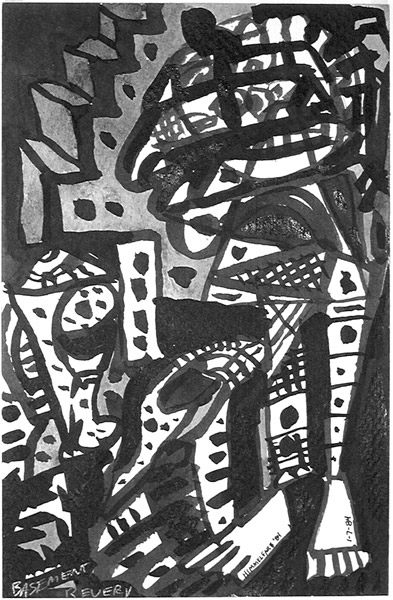

John Himmelfarb’s website describes him as “an established artist whose lush, calligraphic drawings and paintings have always been driven by an unceasing devotion to line. Consistently blurring the boundaries between drawing and painting, Himmelfarb revels in line’s evocative potential to create a synthesis of graphic sign, text and elusive image that challenges one’s ability to interpret visual language.” Many critics, however, would want expand a bit. Christopher Moore, writing in the Christchurch (New Zealand) Press (8/15/2001), saw more than line at play: “John Himmelfarb’s paintings hurl themselves from the wall with a loose-limbed, exuberant, cock-eyed American happiness which demands attention. There’s nothing reclusive or broodingly Calvinist about Himmelfarb’s art. There are instead visual references to improvisational jazz, overhead railways, and stained glass. Above all there is color—eye-trapping panoramas of the stuff, rich tapestries and luminous shards of joyous paint. These are paintings that cause spontaneous smiles on the faces of the most jaded of gallery visitors raised on a diet of sombre introspection and contemporary angst. At 54, John Himmelfarb is firmly established as one of the world's foremost contemporary American abstract expressionists.”

Himmelfarb’s images are not just abstract, however, but often thrust figurative elements in viewers’ faces, yet sometimes slyly tease. Sometimes, as befits a former musician, the rhythms of the work become more important than any other element in their composition in moving viewers to enter into the works. As John Brunetti wrote in the New Art Examiner (December & January, 1996/97), “Himmelfarb’s works suggest several sources of imagination—the formal rawness of the Art Brut and CoBrA movements; the improvisational spirit of automatism; the magical properties of hieroglyphs and totems—channeled into a rich personal vocabulary. Line has always been Himmelfarb’s signature formal element and remains so. Bold contours are applied with both speed and deliberateness in his paintings, drawings, prints, and ceramics to articulate figure from ground, and, of special importance, to create and direct movement. His diverse body of work is unified by an acute sense for orchestrating a continuous rhythm in his compositions. The tempo of each work is carefully dictated through juxtapositions of several weights of line, whose application varies from the delicate, pencil-fine loops of handwritten notations to the bold, paint-dripping boundaries of a three-inch band.” Himmelfarb’s work over the past few years has taken two predominant forms, the lyric paintings in the Inland Romance series and the linear, calligraphic inventions that tease us into thinking there is a language at work that could be understood if we only had a Rosetta Stone to guide us in our translations (there isn’t) like In other words.

Selected Collections: Art Institute of Chicago; Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock; Baltimore Art Museum; The British Museum, London; Mary & Leigh Block Art Museum, Northwestern University; Boston Public Library Print Collection; The British Museum, London, the Brooklyn Museum; the Centre Pompidou and the Musée d'Art Moderne, Paris, France; Cleveland Museum of Art; Des Moines Art Center, Iowa; Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Indianapolis Museum of Art; Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Kalamazoo, Michigan; Milwaukee Art Museum; Minneapolis Institute of Art; National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.; Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea.

Selected One-Person Exhibitions: University of Connecticut, Fairfield (2001); Center for Contemporary Art, Christchurch, New Zealand (2001); Mayers, Aebel, & Mchale, Paris, France (2000); Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago (2002, 2000, 1998, 1996); Sioux City Art Center, Sioux City, Iowa (2000, 1985); Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago (1996); Evanston Art Center, Evanston, Illinois (1996, 1987); Gallery 72, Omaha (1999, 1997, 1994, 1992, 1990, 1987, 1985, 1983, 1979); Terry Dintenfass, New York (1991, 1989, 1986, 1983, 1979); Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock (1990); Miami University Art Museum, Oxford, Ohio (1990); Madison Art Center, Wisconsin (1990); Huntington Museum of Art, West Virginia (1990); Brody's Gallery, Washington, D.C. (1990, 1985); Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Kalamazoo, Michigan (1989); Tallers/Fundacio Josep Llorens Artigas, Gallifa, Spain (1989); Ball State University Art Gallery, Muncie, Indiana (1989, 1978); Blanden Museum of Art, Fort Dodge, Iowa (1986); Davenport Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa (1987); John Nichols, New York (1986); Area X Gallery, New York (1985); Barbara Balkin Gallery, Chicago (1982, 1979); Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska, Lincoln (1978); Illinois Arts Council Gallery, Chicago (1974); Dorothy Rosenthal Gallery, Chicago (1974); Illinois Arts Council Gallery, Chicago (1974); Graphics 1 and Graphics 2, Boston (1974).

|

|

|

|