|

|

|

George Santayana famously said that "those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it" (in The Life of Reason, Vol. I: Reason in Common Sense). The question, of course, is which past are we supposed to remember, immediate, middle distance, ancient? And what are we to do with our memories? Let us begin with the memories depicted in Goya's great print series, Los Caprichos, the Disasters of War, and the Proverbios.

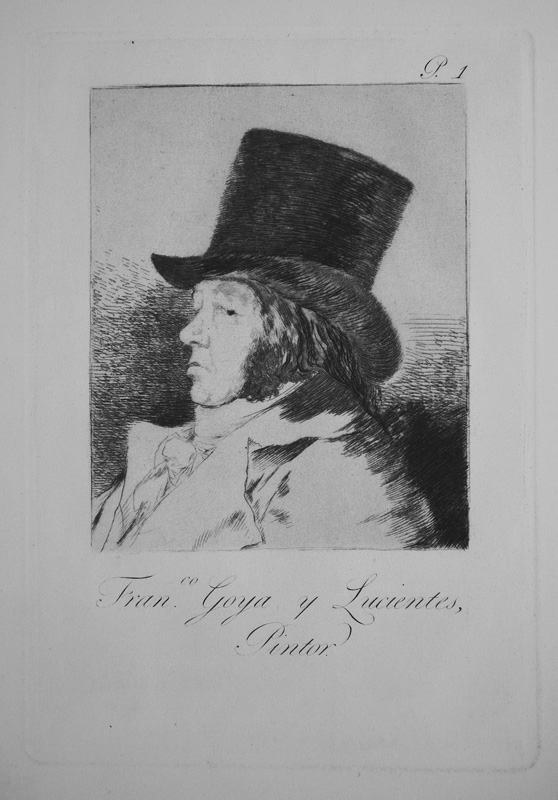

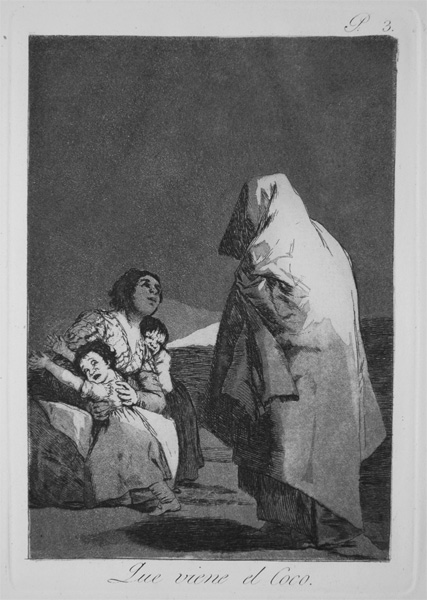

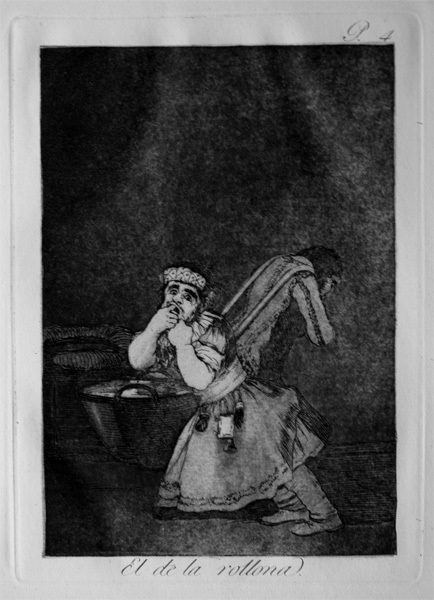

The eighty etchings that make up Goya’s most important series of prints, Los Caprichos (1799), have long been recognized as one of the supreme monuments of European art. Goya, royal painter to the kings of Spain during the late eighteenth-early nineteenth centuries, eventually died in exile, both of his major print series having been "donated" to the crown to protect him from the Inquisition. A believer in the potential power of reason, his works show what happens when reason is trampled underfoot by individual human follies and corrupt social customs. In these works Goya looks at his country and memorializes it as a monument to desperation, folly, arrogance, incompetence, and the need that some of his subjects have to try to control the uncontrollable. Spaightwood has a complete set (from the sixth edition—an edition we first saw presented in an exhibit of Goya’s works at the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, Germany); we will show the entire series of 80: almost all in impressions from the sixth edition, but with a scattering of pieces from the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th editions as well. We also include several impressions from the Disasters of War and one of the Proverbios.

In the Foreword to his edition of Goya's Complete Etchings, Aldous Huxley (whose Brave New World offers a fairly bleak view of the fates of men and women in a world ruled by monsters), summarized Goya's portrayal of his world in his "Later Works" (which include all of Goya's major etching series: "These creatures who haunt Goya's Later Works are inexpressibly horrible, with the horror of mindlessness and animality and spiritual darkness. And above the lower depths where they obscenely pullulate is a world of bad priests and lustful friars, of fascinating women whose love is a 'dream of lies and inconstancy,' of fatuous nobles and, at the top of the social pyramid, a royal family of half-wits, sadists, Messalinas and perjurers. The moral of it all is summed up in the central plate of the Caprichos [originally plate 1], in which we see Goya himself, his head on his arms, sprawled across his desk and fitfully sleeping, while the air above is peopled with bats and owls of necromancy and just behind his chair lies an enormous witch's cat, malevolent as only Goya's cats can be, staring at the sleeper with baleful eyes. On the side of the desk are traced the words, 'The dream [or 'sleep'] of reason produces monsters.'" While perhaps not the last words on the Caprichos, these offer a very good first response to the series, one that can only get richer and more complicated as we look again and yet again at the works.

Select Bibliography: Rogelio Buendia Goya (NY: Arch Cape Press, 1990), Jean-François Chabrun, Goya: His Life and Work (NY: Tudor, 1965), Colta Ives & Susan Alyson Stein Goya in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995), Dagmar Feghelm, I, Goya (Munich: Prestel, 2004); Raymond Keaveney, Master European Paintings from the National Gallery of Ireland from Mantegna to Goya (Dublin: National Gallery Of Ireland, 1992), Fred Licht, Goya and the Origins of the Modern Temper in Art (NY: Harper & Row, 1983), Park West Gallery. Goya: Sleeping Giant (Southfield MI: Park West Gallery, n.d.), Alfonso E. Perez Sanchez, and Eleanor Sayre, Goya and the Spirit of the Enlightenment (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1989), Maurice Raynal, The Great Centuries of Painting: The Nineteenth Century. New Sources of Emotion from Goya to Gauguin (Geneva: Skira, 1951), Richard Schickel, The World of Goya 1746-1828 (NY: Time-Life Books, 1968), The Royal Academy of Arts in London, Goya and his times (London: Royal Academy, 1963), Janis A. Tomlinson, Goya in the Twilight of the Enlightenment (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), Juliet Wilson-Bareau & Manuela B. Mena Marqués, Goya: Truth and Fantasy. The Small Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

Works on Prints: The standard catalogue raisonnes of Goya's prints by Loys Delteil and Tomas Harris (Goya Engravings and Lithographs, 2 vols., rpt. ed. 1964) are both out of print. See Nigel Glendinning, Goya: La Década de los Caprichos. Retratos 1792-1804 (Madrid: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Francisco, 1992), Verna Posever Curtis and Selma Reuben Holo, La Tauromaquia: Goya, Picasso and the Bullfight (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum, 1986), Anthony H. Hull, Goya: Man Among Kings (NY: Hamilton Books, 1987), Aldous Huxley, ed., The Complete Etchings of Goya (NY: Crown Publishers, 1943; Huxley incorporates Goya's own comments on the Caprichos from a manuscript now in the Prado in Madrid, many of which I have incorporated in my descriptions; more frequently I have used the translations in the Dover Edition (NY: Dover Publications, 1969) of Los Caprichos; R. Stanley Johnson, Goya: Los Caprichos (Chicago: R.S. Johnson, 1992; Johnson usefully cites remarks of an early commentator on Goya from a manuscript preserved in the Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, some of which I have incorporated in my descriptions), Elie Lambert, Goya: L'oeuvre grave (Paris: Alpina, n.d.), Roger Malbert, ed. Disasters of War: Callot, Goya, Dix (London: Cornerhouse Publications, 1998), Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, & Julián Gállego, Goya: The Complete Etchings and Engravings (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1995), Nicholas Stogdon, Francisco de Goya, Los Caprichos: Twenty Proofs and a New Census (London: N.G. Stogdon, Inc, 1988), Janis A. Tomlinson, Graphic Evolutions: The Print Series of Francesco Goya (NY: Columbia University Press, 1989).

|

|

|

|

|