|

First, I believe that a person is an artist not necessarily by the grace of God—but, well yes . . . by genetics . . . by force of character. Then . . . given that anything is possible and that everything has already been done, that we have had a total liberty to create since Dada and Duchamp (there’s nothing left to destroy), that the academy and academics are totally outdated . . . Then (given all this) . . . the artist has to choose [what] (a subject) and [how] (a technique).

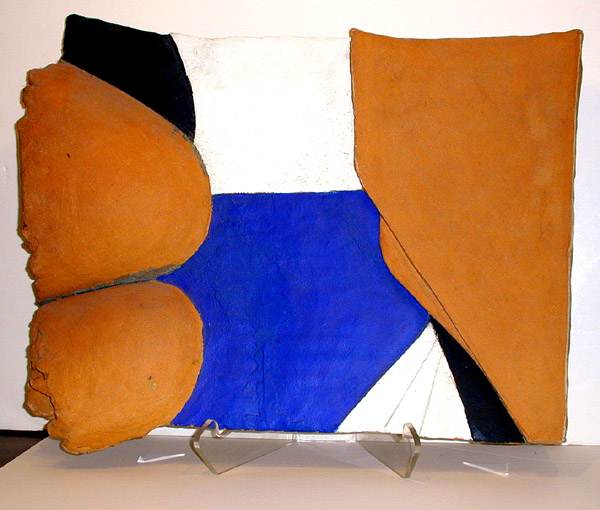

It is rare to find great works in the history of art that do not have at their origin a profound motivation, be it religious, nationalistic, social, or even personal. In my case, the choice was made almost "automatically." Not being a believer, God could not help me. Not having any particular political sympathies because I am too critical of all of them, I could not be nationalistic. The creative adventure, then, became for me one of eroticizing the world: this desire, nonetheless, attenuated by something I have inherited from my father and from Miró, a taste for work and the pleasure of the raw materials of my work.

For me, it is evident that you cannot do the same work, create the same piece twice with earth, stone, and bronze. Each materia, having its own characteristics, must be respected for its individuality. If you sculpt the same piece twice with different materials, one of these will undoubtedly be bad and it will also be the one that did not take into consideration the possibilities of the material chosen. (In other words, you cannot play the same music on any kind of instrument.) So—for any beginning artist, especially a sculptor, the fundamental problem is that of choosing the kind of medium in which to work. This might not be the essential problem, but it is the one which will determine all his or her future creations. He might therefore say that it is, indeed, the essential problem.

Now—why eroticize the world? If I were not Spanish, educated during the reign of Franco, in a Catholic environment in a state of extreme decadence, with institutionalized intolerance all around me, perhaps I would not be the artist I am with the concerns I have. But it was like that and I am who I am. I eroticize the world to de-dramatize the subject, to strike down taboos, to prove that what "they" told us was ugly is, in fact, beautiful. I eroticize the world—especially—to take on a dangerous subject. There is no "beauty" without ulterior motives. There is no longer ugliness or beauty, good or evil; THERE IS, that is all. And sex (and sexuality) exist—they are approached differently according to different countries, different cultures—but everywhere sex is immense, the source of the future, of beauty, of passion.

And as for the "subject": if the artist has a personality the subject must disappear in the work (otherwise the result is decoration, "decorative art"). When Giacometti sculpts a woman, the result is a sculpture by Giacometti, not a woman. We learn more about Giacometti from that sculpture than about the woman sculpted by him. The subject must serve only as a support, a point of reference: that is why almost all artists willingly limit their choice of subject matter—to give them more strength. The goal, then, is not the beautiful but the true and not truth in the eyes of others but truth in regard to oneself.

For a plastic artist, it is not a matter of speaking but of doing. The work only exists when it exists , because if it is only spoken about, it remains literary, which in my opinion is a serious error. To speak or to do, the ephemeral or the concrete: there is not much to say but so much to do. I think that every work which has ever been created takes much greater effort to be destroyed. That is, after creation the work has its own life which totally escapes the artist, and . . . that is good because that is what permits him or her to advance, to progress. Using as a base a definite knowledge, a definite mastery of the métier, every creator must subvert the subject. It’s a matter of breaking the structure—but this is based on " . . . " When the surrealists speak about assassinating painting, it’s obvious that the " . . . " is the basis or point of departure for the assassination because their means of expression is painting or literature.

Just as the choice of subject presents itself so does the choice of techniques. One must ask: "For this project, should I transform it into a sculpture, a drawing, an engraving, or a lithograph?" At this point one’s mastery of techniques comes into play. If I want power, impact, a startling image, I use lithography. With the technique of printing directly off the stone, it is possible to get a maximum of ink on the paper. This direct impression from stone or zinc allows the kind of powerful color that is impossible to get with an off-set process. (Think, for example, of the strength of Toulouse Lautrec’s posters.) If, on the other hand, I want a secret image with a magic quality, I turn to etching. The pressure of the damp paper will insure that the intensity of the black, the relief of the features etched on the copper will remain on the paper, giving it a richness and a finesse that forces us to look closely at it, making us wish to hold the etching in our hands, to feel the quality of the paper. The result is a work more secret, more intimate—more precious.

When the concern is creating a sculpture for a specific location, it is obvious that the first thing to do is to study the site. An urban landscape, the open-air environment of the country, a highway, a huge space or a small one sets the conditions for the sculpture—both its dimensions and its form, even its color. The sculpture can be implanted by opposition to the environment as well as through integration with it. In fact, the location, the site, dictates at least 50% of what the work will be; but it is always, in the end, based on that " . . . " A " . . . " that, little by little, bit by bit, because of the work undertaken, grows and becomes richness itself.

To conclude, if there were a magic key to open doors and explain everything I do, it would be the one opening onto hard work and the pleasure of doing and of choosing an ambitious project. And a sense of humor, too—because, after all, we should not forget that none of this is very serious.

This is the translated text of a speech delivered by Joan Gardy Artigas at the Elvehjem Museum of Art of the University of Wisconsin—Madison on 3 May 1982. It is used here with the permission of the artist and the translator, Judith G. Miller.

|

|

|