|

Bodmer was born in 1809 in Zürich, Switzerland. When he was thirteen years old, his mother’s brother, Johann Jakob Meier, became Bodmer’s teacher. Meier was an artist, having studied under the well-known artists Heinrich Füssli and Gabriel Lory. Young Bodmer and his older brother, Rudolf, joined their uncle on artistic travels throughout their home country. By 1828, Bodmer had left his native Switzerland for the German city of Koblenz. It was there that he came to Prince Max’s attention. After delays, Bodmer, in the company of Prince Max and a huntsman and taxidermist, David Dreidoppel, set out for America on 17 May 1832. In a letter bearing that date, Prince Max wrote to his brother that Bodmer “is a lively, very good man and companion, seems well educated, and is very pleasant and very suitable for me; I am glad I picked him. He makes no demands, and in diligence he is never lacking.”

According to William J. Orr’s section on “The Artist’s Life” (in William Goetzmann, et al, Karl Bodmer’s America (Omaha: Joslyn Art Museum and University of Nebraska Press, 1974), “Karl Bodmer’s life is essentially the story of a fortuitous episode. In no way does it conform to the romantic image of the artis as indomitable genius, destined to emblazon his name on the pages of history. He was rather a precocious and conscientious draftsman who had embarked upon what promised to be a distinguished though not illustrious career when, suddenly and unexpectedly, he was offered the opportunity to travel to the remote reaches of a wild and distant land. Faced with countless hardships and exotic subjects, he rose to the challenge, creating ethereal landscapes and serene portraiture of delicate and ethereal beauty. Yet once this assignment was completed, he reverted to more conventional themes, largely bereft of daring and inspiration. Never again would his art achieve that novelty and brilliance so abundantly reflected in this brief phase of his lifework” (p. 351). This very formulation, however, seems based upon a romantic conception of the nature of the work of the artist, a conception that the English Romantic pet Percy Bysshe Shelley would have approved.

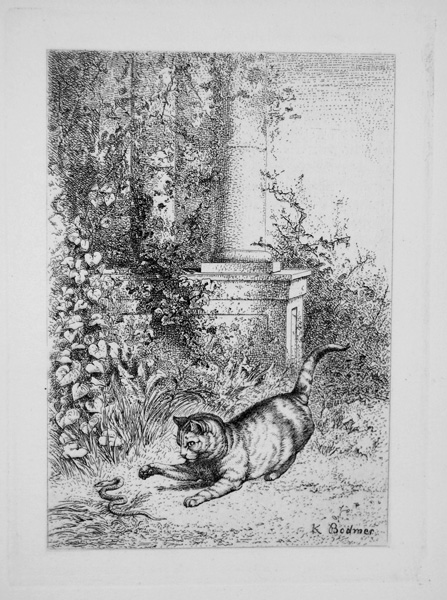

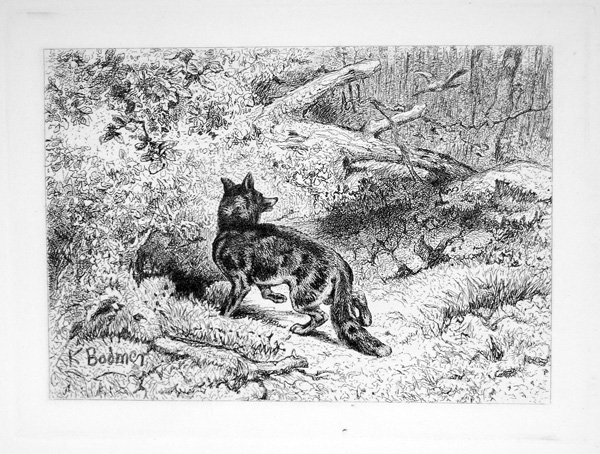

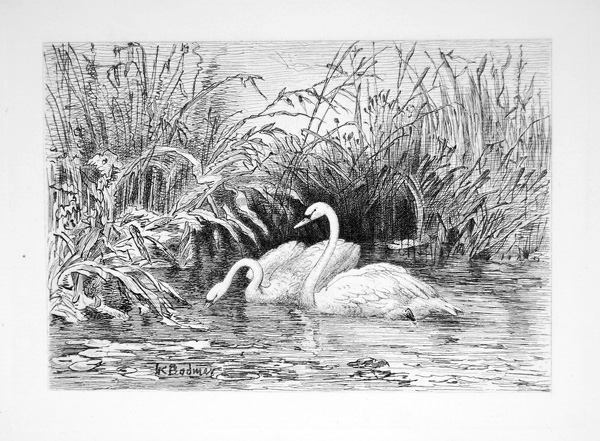

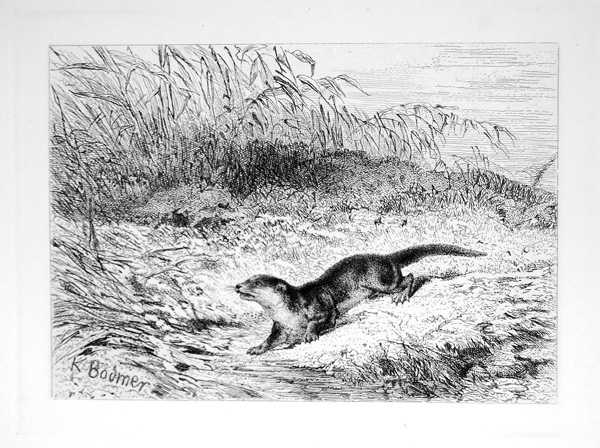

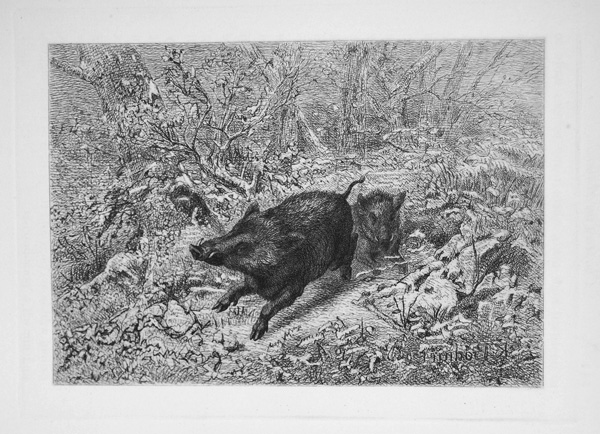

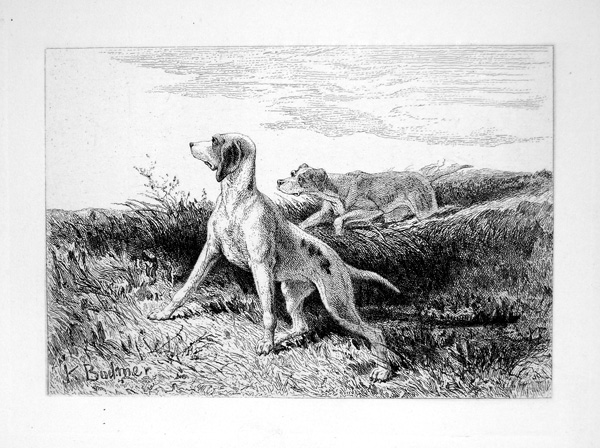

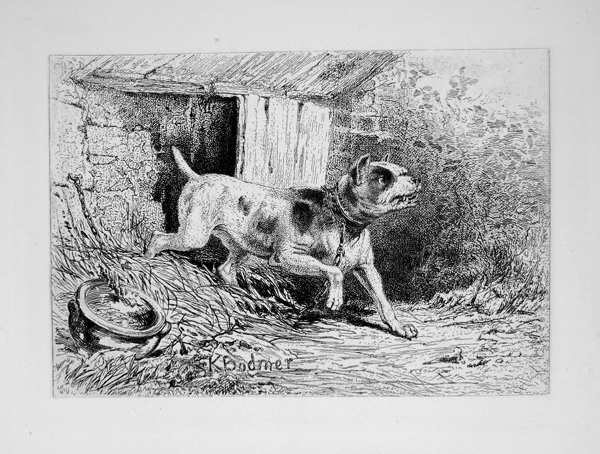

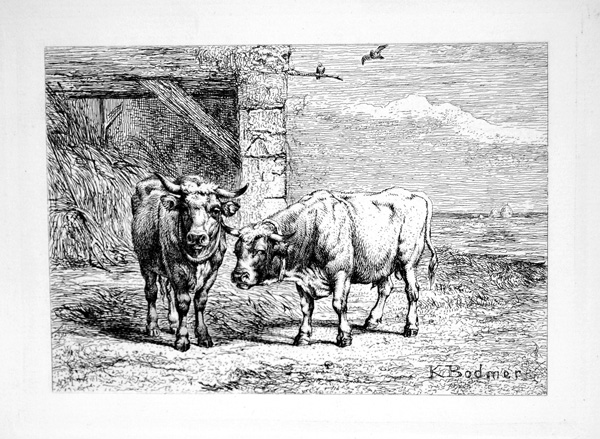

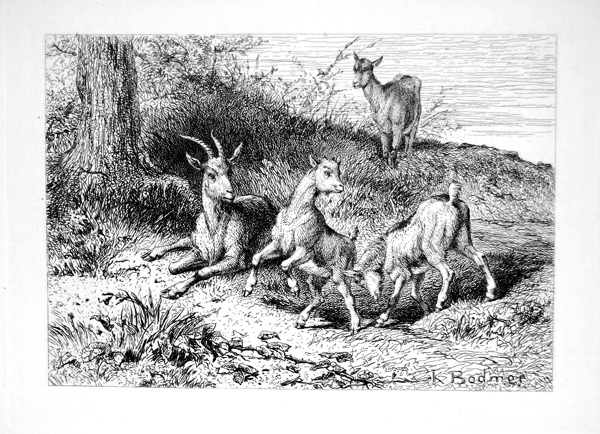

At the root of Orr’s complaint seems to be Bodmer’s post-expedition subjects: the animals and landscapes of his new home in Barbizon, France, bordering the forest of Fontainebleau. Orr, talking about Bodmer’s portraits of Native Americans, praises his “superb fidelity to detail” (p. 358), yet contrasts that to the “sometimes insipid themes of his later career” (p. 358),the animals and landscapes of his adopted country, France. Bodmer, however, in a letter to Prince Max, declining his invitation that Bodmer accompany him to Egypt, insisted that “Animals and the forest are my favorite theme, to which I wish to commit myself entirely” (p. 365). Philip Hamerton, author of Etching and Etchers, appearing in numerous editions from the 1860s on, praised Bodmer as “an artist of consummate accomplishment in his own way, and of immense range. There is hardly a bird or quadruped of Western Europe that he has not drawn, and drawn, too, with a closeness of observation satisfactory alike to the artist and the naturalist. The bird or beast is always the central subject with Karl Bodmer, but he generally surrounds them with a graceful landscape, full of intricate and mysterious suggestions, with here and there some plant in clearer definition, drawn with perfect fidelity ad care” (pp. 368-69).

Bodmer in fact was recognized for his French landscapes, exhibiting regularly at the Paris Salon beginning in 1850, and winning several prizes. Theophile Gautier, an important art critic, praised one of his 1850 paintings as “ ‘possibly the most beautiful landscape’ in the exhibition" and the reviewer for L’Artiste acclaimed him as “on the level of the most formidable landscape painters" (p. 366). He received the ultimate recognition from the French government in 1876 when he was awarded the “coveted” Legion of Honor (p. 367). Bodmer was also a prolific engraver whose works were published in popular art magazines, important art journals, and deluxe illustrated books.

Selected bibliography: The most important study of Bodmer to date is David C. Hunt, William J. Orr, W. H. Goetzmann, ed., Karl Bodmer's America (Omaha : University of Nebraska Press for the Joslyn Art Museum, 1984); see also Brandon K. Ruud , ed. With Ron Tyler and Marsha V. Gallagher, Karl Bodmer's North American Prints (Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 2004); Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied, Maximilian Prince of Wied’s Travels in the Interior of North America, during the years 1832–1834 (London: Ackermann & Co., 1843–44; John C. Ewers: Views of vanishing frontier. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha (Nebraska) 1984 + 1985; Marsha V. Gallagher: Karl Bodmer’s eastern views. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha (Nebraska) 1996; Philip Gilbert Hamerton: The Portfolio, Vol. 1-2. With Illustrations by Karl Bodmer (London 1870); Clyde Hollmann, Five Artists of the Old West: George Catlin; Karl Bodmer; Alfred Jacob Miller; Charles M. Russell; Frederic Remington (New York: Hastings House, 1965); Victor Hugo, Quatrevingt treize. Dessins de Emile Bayard, G. Brion, Karl Bodmer, Gilbert Riou et al. (Paris: Claye, 1877)W. Raymond Wood, Joseph C. Porter, David C. Hunt: Karl Bodmer’s studio art: The Newberry Library Bodmer Collection (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002); Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied: Reise in das innere Nord-Amerika in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834, 2 vol. (Koblenz, 1840-41. Reprint of L. Borowsky, München, 1979); Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied: Verzeichnis der Reptilien welche auf einer Reise im nördlichen America beobachtet wurden (Salt Lake City: Bibliomania!, ca. 2006).

|

|

|